As Halloween comes to an end, Conor Bryce keeps the scares coming, as he looks at the top ten key moments of classic cinema that were secretly horror films.

10. Raptors in the kitchen, Jurassic Park (1993)

Forget the T-Rex stomping its way through the rain; the real slow-burn terror in Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park arrives when two velociraptors, with all the predatory grace of ballet dancers and the problem-solving tenacity of MIT grads, hunt two children through the cold, stainless-steel maze of a visitor centre’s kitchen. The sequence is a masterclass in escalation. The kids, Lex and Tim, are trapped in a space designed for utility, surrounded by metal surfaces that betray every step. The raptors, meanwhile, aren’t lumbering movie monsters like the other park inhabitants; they’re intelligent, relentless and, crucially, even playful.

Many blockbusters – especially those with a PG-13 rating – would have settled for a quick, noisy chase. Instead, Spielberg encourages his audience to squirm. The raptors squeak and open doors. They tap their razor-sharp talons, as if pondering the most efficient solution to the puzzle of “how do I eat these children?” The camera lingers on the slow, surgical dismantling of safety. Lex and Tim scramble, using only their wits and a handful of kitchen implements to outmanoeuvre creatures that, hours earlier, were mere exhibits behind glass.

Jurassic Park is marketed as adventure, dressed in the trappings of family-friendly spectacle. Children in danger is a narrative taboo that most blockbusters treat with kid gloves, but here Spielberg is precise. Every clang of a ladle, every reflection in brushed steel, is meticulously placed to maximise suspense without ever tipping into cliché. This terror is where Jurassic Park stops being a movie about humans controlling nature and becomes a movie about nature controlling humans. Long after the credits roll, it’s not the T-Rex that stalks your dreams – it’s the rap of claws against linoleum, and the knowledge that even in the kitchen, nobody is safe.

9. The Fireys want to play, Labyrinth (1986)

There’s a particular sequence in Labyrinth that sneaks up on you. The film, after all, is ostensibly a lavish fantasy adventure – a Jim Henson concoction filled with puppets, sparkly costumes and the ever-magnetic David Bowie waggling (careful now) his way around a crystal ball as Goblin King Jareth. Yet nestled among the whimsy is a scene that feels like it wandered in from a far stranger, darker movie. I’m talking, of course, about the Fireys: a feverish burst of unhinged menace that, in a film full of oddities, stands alone as a moment of pure, undiluted chaos.

For those who haven’t revisited Labyrinth since childhood, let’s set the scene. Sarah, far from her safe, petulant bedroom, stumbles into a forest clearing only to find herself encircled by the Fireys – a troupe of lurid, shaggy creatures who treat their own bodies as a set of detachable party favours. At first, there’s a slapstick edge to their antics. Heads are flicked off like bottlecaps, legs and arms tossed about with gleeful abandon. But what begins as clowning morphs into something much more predatory, as the Fireys turn their attention to Sarah. “Hey! Her head doesn’t come off!” they puzzle. “I know what we can do!” one then cries, as they close in with a logic as surreal as it is coercive: “Take off her head!”

The Fireys don’t just want to party; they want Sarah to join them, to be remade in their own insane image, to literally take herself apart. Their physicality is wild and unpredictable, their bodies breaking and reassembling with a disregard for the rules of anatomy. Suddenly, Sarah is hemmed in on all sides, the Fireys’ arms and legs multiplying like a fever-dream game of Twister, their insistence crossing into threat.

There’s a reason this scene continues to haunt those who encountered it as kids. Unlike the film’s more obvious villains – Jareth, with his glam-rock charisma and clear motives – the Fireys are anarchy incarnate, the embodiment of fun gone wrong. Their menace is slippery; they don’t want to kill Sarah, exactly.

The technical wizardry on display amplifies the unease. The Fireys’ movements are jerky in their artificiality, rendering them alien in a world otherwise teeming with tactile, felted creatures. The scenes were achieved through a blend of puppetry and blue-screen technology – fascinating from a production standpoint, but in practice, the effect is a glitch in the fabric of the film, an uncanny valley that the Fireys gleefully inhabit.

What’s most striking is that there’s no blood, no fangs, no jump scares. And yet, the Fireys’ pursuit gives a nod to the tense escalation of a psychological thriller. Their numbers swell as Sarah tries to escape, their laughter ringing out. It’s a moment where the film’s central anxiety – what happens when the world stops making sense – crystallises into something very dark indeed.

8. The Ark is opened, Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)

When the Ark of the Covenant finally opens in Raiders of the Lost Ark, what unfolds is darker than your typical climax of an adventure movie. A pulp-fed romp through Nazi-punching and snake-pits suddenly stops grinning and remembers what it’s playing with: the divine. It’s one of the more terrifying scenes that Steven Spielberg (him again) ever directed, including anything with a shark.

The build-up is sinister fascist pageantry. Bound and surrounded, heroes Indiana Jones and Marion Ravenwood watch as the villains conduct a ritual akin to bureaucrats undergoing a séance. The Nazis line up, arch-nemesis Belloq dressed as a high priest of sorts. Indy is a voice in the dark, telling Marion not to look. Then the lid of the Ark – a container for the holiest of holies, the Ten Commandments – is lifted, and soft, beautiful spirits drift free.

For a few seconds, the luminescent, floating spectres deliver a sense of Disney whimsy. Then the light changes, and what follows is pure nightmare alchemy. Faces melt like wax effigies in a temple inferno; eyes boil; every proud, power-hungry sneer liquefies when faced with His judgement.

That’s what makes the moment enduringly unsettling – it’s grotesque, yes, but the real violence is theological. The Ark answers with an older logic, perhaps the oldest: f**k around, find out. Technically, it’s perfect pop terror. The pacing is patient, the effects tactile, the compositions austere. Even the movie’s closing punchline – that the Ark ends up boxed in a government warehouse – feels like the start of a ghost story. You can shelve the void, but you can’t destroy it. The final image of Indy and Marion, shaken from the cost of watching the gruesome fallout of playing God. Well, by trying to play God.

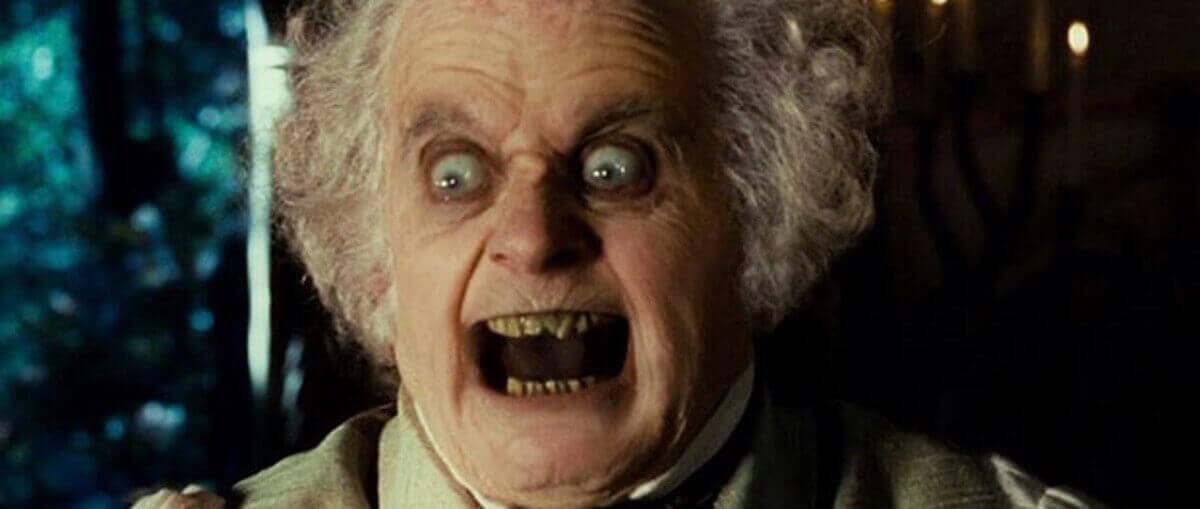

7. Bilbo’s greed, The Fellowship of the Ring (2001)

The Lord of the Rings changed cinema forever when the first in its series, The Fellowship of the Ring, landed in cinemas in 2001. Director Peter Jackson practically pulled off a miracle by both filming the unfilmable novels and packing them with gorgeously realised fantasy and never-seen-before epic battles. A horror legend long before he set foot in Middle-earth, Jackson also managed to include several moments that fuelled our nightmares. The most memorable, one still talked about today, comes from one of Middle-earth’s most unscary characters, a certain Master Bilbo Baggins.

The scene unfolds with an almost casual intimacy. We’re in Bilbo’s cosy hobbit-hole, surrounded by the comfort of pipe smoke and the soft rustle of worn books – a setting that encourages ease and a sense of security. Then, a subtle shift begins. The easy camaraderie frays as Bilbo’s gaze fixes obsessively on the Ring, the camera tightening, the light dimming just so. What follows is a morphing of the familiar into something uncanny: Bilbo’s face contorts, the warmth draining away, replaced by sharp shadows and an expression that’s less hobbit, more something grotesque lurking beneath the surface. It’s a physical manifestation of addiction, the Ring’s corrosive power made visible in writhing facial muscles and wild eyes.

The fact that it’s a very nasty, very effective jump scare that has no place here should be enough for it to resonate, but that it’s passive, loveable Bilbo scaring us makes it all the more effective. The Ring has the power to twist and corrupt its past owners long after they thought they’d escaped its lure; Bilbo will never be free of its dreadful siren’s song. That’s what gives the moment its queasy longevity. The chef’s kiss is Bilbo’s reaction immediately after lashing out; cowering back, pleading with Frodo to forgive him, sobbing at his uncontrollable actions. Absolutely devastating.

It’s easy to overlook this tiny scene amid the elf feasts and wizard duels, but it distils the central terror underpinning Tolkien’s saga – corruption is a slow trickle. When Bilbo’s face distends, it’s the Ring whispering its universal truth. After seeing this hobbit’s distorted face, we can’t quite look at Bilbo the same way again.

6. Boat ride from hell, Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (1971)

Gene Wilder doesn’t wink at you in the tunnel scene of Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory - not really. What he does is infinitely stranger. As the river boat slithers into darkness, Wilder’s irises catch the coloured lights like twin pinpricks of knowing malice. His face, usually all enigmatic charm, compresses into something unreadable, cycling through joy, fury, madness, and maybe, just maybe, glee. For a moment, children’s cinema forgets it’s supposed to be kind.

At first glance, the ride is playful, almost trancelike. The children and their guardians board a small boat, drifting gently along a murky chocolate river inside the factory’s depths. But as the boat slips under the tunnel, the atmosphere shifts. Wonka’s cryptic, off-kilter narration merges with a barrage of psychedelic imagery - flashes of faces, swirling colours, distorted sounds - that assault the senses. It’s a sensory overload that feels less like a tour and more like a journey through a hallucinatory nightmare.

It’s a disorienting, claustrophobic ride where the visuals spill over in a kaleidoscopic mess: faces morph grotesquely, shadows twist, and the soundtrack’s eerie tune underpins a frantic tension. The children and the adults plead for the journey to halt... but Wonka’s strange poetic performance intensifies.

What makes the boat ride effective as a scary set piece is its radical tonal departure. Up until this point, the film has been a technicolour romp with a mischievous Wonka guiding the way. Suddenly, this sequence feels like an intrusion of chaos. To misquote Mr Wonka, a little abject horror now and then is relished by the wisest men.

5. The secret of Pleasure Island, Pinocchio (1940)

The scene in Pinocchio where Pleasure Island’s boys sprout hooves and bray like beasts is a descent into hell: the moment the movie quietly abandons its wooden hero to focus on a transformation sequence that would make David Cronenberg flinch. The island, with its cotton-candy name and carnival grin, weaponises delight. The boys are getting exactly what they want - no school, no rules. The bill doesn’t come due until the room goes quiet and the ears start to grow.

The scene operates like a con. The lighting shifts from brassy amusement park-gold to damp blues and sickly greens. The sound design does the rest: raucous chorus fading to hollow echoes, distant brays bleeding into the mix, a panicked heartbeat of drums. The fate of Pinocchio’s companion Lampwick is the worst; a slow, moral panic attack. First the tail, then the hooves, then the voice collapsing into a howl. He grabs for human language and can’t find it. That’s the stuff of pure nightmare. The most disturbing part? His last words before his voice goes full raucous bray are a scream for his mama.

Animation provides a rubbery elasticity that live action would have softened. Bodies distort in grotesque increments. The lens creeps closer as Lampwick pleads with a broken cigar hanging from his lips. You think of all the cautionary folk tales about bad company and giving in, only here the parable not only wags a finger, but insists on snapping the finger off and tossing it in a crate marked Property of the Coachman.

Ah, the Coachman: managerial evil in a bowler hat. The logistics of his operation are an unspoken horror. The empty streets, the smashed amusements, the black-coach convoy, the gloved henchmen corralling sobbing donkeys - industrial-scale punishment dressed as a field trip. Pleasure Island is capitalism’s funhouse mirror: fun as the hooked worm, child labour as destiny. As a scare sequence, it’s exquisitely paced. The earlier island antics lull the audience into thinking they’re watching comic misbehaviour. Even the escape feels compromised. Pinocchio flees, but the island keeps its inventory. Lampwick’s fate hangs over the film.

The moment also hums with cultural residue, a warning about boyhood impulses channelled through the grammar of horror - the existential dread of becoming something you can never unbecome. In the pantheon of scary scenes smuggled into non-horror films, Pleasure Island stands out because it understands the oldest trick in the book: punishment lands hardest when it masquerades as a gift. The carousel goes round, the lights wink out, and the donkey brays echo into a night that suddenly looks never-ending.

4. Toxic waste bath, Robocop (1987)

Few moments in 1980s action cinema catch audiences as unprepared - and as queasily transfixed - as the one in the climax of Paul Verhoeven’s Robocop when Emil, one of villain-in-chief Clarence Boddicker’s black-leathered goons, hurtles into a vat of industrial waste. It’s brilliantly gross and unforgettable. One second, Emil’s all sneering bravado in his cheap leather jacket. The next, he’s flailing in a vat of something that glows like malevolent Miwadi. Robocop plays its hand with brutal efficiency: it’s satire, right up until the moment it dumps a man into industrial solvent and forces you to watch him liquefy.

What unfolds is less a death scene and more a perverse biology lesson. Practical effects maestro Rob Bottin conjures a spectacle where skin sloughs off like wet paper, bones soften, and the human form collapses under its own dissolving weight. The toxic sludge bubbles with a sick luminescence. There’s no dignity, just a wet, gargling collapse into biological chaos... latex, corn syrup, and nightmare fuel. You can practically smell the acrid stench of synthetic decay.

And then, the punchline. Stumbling blindly onto the road, a shambling monument to corporate by-products, Emil steps into the path of his own boss’s speeding sedan. Splat. The abruptness is the kicker, delivered with deadpan coldness. It’s horrifying, yes, but the sheer, absurd suddenness tips it into a realm of gallows humour. Clarence Boddicker barely brakes. Why would he?

Decades later, that wet, desperate gurgle still echoes - a terrifying splash of cold sludge in the face of slick, 1980s action cool. Pure Verhoeven. Pure horror.

3. Artax gives up, The NeverEnding Story (1984)

Cartoonish melting criminals and malicious Muppets are one thing, but there’s always room for some existential dread on this list. And yes, does this scene go there. There’s a small corner of childhood cinema that feels engineered to emotionally scar a generation, and this sits enthroned near the peak.

The NeverEnding Story is a complex, sophisticated exploration of nihilism, creation and despair, disguised as a kid’s movie. It’s got its fair share of scary elements: a huge black wolf relentlessly hunting our hero, fiery death rays and a void of nothingness literally swallowing existence. But nothing comes close to the sad death of hero Atreyu’s beloved horse and companion, Artax.

Animal death is always unpleasant, but Artax’s demise is particularly bad. Hero and horse slowly make their way through the Swamp of Sadness, named for its nature to swallow travellers who give up hope. One step too heavy and you’re pulled under. While Atreyu just about manages to keep himself afloat – physically and emotionally – his trusty steed isn’t so lucky. Yes, Artax the horse gets depressed and drowns. Tension builds through geography too: framed wide, the swamp looks endless; in tight, it’s a trap. The mudline creeps upward, and practical effects make it so tactile.

There are solid reasons why this is so horrifying. Putting aside the fact that a horse literally dies of sadness, Atreyu begs with Artax to keep going, to not give up. And while his sobbing, screaming grief is a gruelling watch, it doesn’t hold a candle to some amazing animal acting. Somehow, Artax looks confused, then scared, then resigned. As he slowly slips to his death, his dark eyes meet Atreyu’s.

What seals its status as nightmare fuel is the moral geometry. Atreyu is brave, devoted, and yet the swamp claims its victim anyway. This young boy learns that not every plea can rewrite the world. Now, that’s horror.

2. The Child Catcher, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968)

The O.G. cinematic boogeyman. Disney’s Chitty Chitty Bang Bang may not be as beloved as, say, Mary Poppins or Bedknobs & Broomsticks, but it does have an ace in the hole: a villain who’s top of the charts for scariest of all time, despite only getting around five minutes of screen time – the Child Catcher.

Tiptoeing into a candy-coloured dream, he salts it with dread. One minute we’re in a confectioner’s window, the next we’re staring down a fable about state-sanctioned terror and grand theft auto. In Chitty Chitty Bang Bang’s movie-within-a-movie, inventor – and single father – Caractacus Potts regales his children with a fairy tale about the tyrannical Baron of Vulgaria, who tries to steal the eponymous car. In the story, the Baron has banned children from his kingdom, leading to a terrifying sequence with the Child Catcher being dispatched to hunt down any rogue kids.

The Child Catcher is an enforcer for a despot, capturing then imprisoning children. The creepy, high-pitched voice. The exaggerated facial features, including a long nose for smelling his quarry. The way he moves like a dancer (actor Robert Helpmann bringing his ballet experience to the role), all lithe sneaks and creeps.

There’s also rich symbolism at play – his promise of sweets and funfairs hiding a sinister fate taps into our childhood ‘stranger danger’ fears. It's been hailed as an allusion to the Gestapo, especially given that creator Roald Dahl fought in World War II (although it’s also worth mentioning that Dahl came under criticism for the villain bearing some antisemitic stereotypes). And last but not least, the Child Catcher loves his job. He lives for it.

The real genius of the Child Catcher’s design is that he’s terrifying to both children and adults, for entirely different reasons. He delivers the same chill you get from tidy officials – the ones who always use ‘the rules’ as a weapon – in other properties, from Nurse Ratched to Dolores Umbridge. Chitty Chitty Bang Bang never quite reclaims its tone after the Child Catcher appears.

Half a century later, audiences have seen far darker threats and far bloodier ones, yet few have left such a subtle bruise. A brilliant combination of uncanny visuals, manipulative behaviour and deep psychological fears, the Child Catcher is the perfect villain.

1. Every single godless minute of Return to Oz (1985)

Let’s just get this out of the way now: Disney (!!!) kids' movie Return to Oz is perhaps the most audacious, unintentional horror film ever made. Forget the ruby slippers and skipping down yellow brick roads; this long-gestated sequel plunges Dorothy Gale headfirst into a waking nightmare, swapping Technicolor whimsy for a dread-soaked, sepia-toned hellscape that would unsettle Clive Barker. It’s a masterclass in childhood trauma disguised as family entertainment.

Every digital copy of it should be erased, forever. Every physical copy should be melted in toxic waste, and the goopy, evil remains then stuck on a rocket and shot into the sun. Practically every minute of its unholy runtime is festooned with the kind of nightmare fuel that would give Freddy Krueger cold sweats. Let’s have a look, shall we?

Our reintroduction to Dorothy isn’t through a sunny Kansas farm, but a grim psychiatric asylum. Aunt Em, driven to despair by the girl’s ‘delusions’ of Oz, subjects her to electrotherapy. The doctors coo about currents, the storm rages, and the power goes out mid-procedure. This isn’t subtext; it’s the opening scene, presented in full – a child, strapped to a table, facing forced treatment for believing in magic.

When Dorothy eventually returns to Oz, the cheerful Munchkins are reduced to petrified stone statues. The Emerald City is a crumbling ruin under the shadow of the Nome King, a subterranean tyrant whose preferred method of interior design involves turning living beings into ornaments. And the threats Dorothy encounters are ripped straight from a Freudian sketchpad. The Wheelers, with their shrieking laughter and terrifying, clattering wheel-hands, are the embodiments of relentless, mechanised pursuit. Princess Mombi, residing in a palace of mirrors, elevates the status of vain antagonist to body horror icon. Mombi's quest for beauty involves collecting the heads – the heads – of young women, displaying them in glass cabinets, swapping them onto her own neck with the wet smack of detached flesh. Imagine explaining that to a six-year-old.

The film’s macabre inventiveness never relents. Tik-Tok, the clockwork soldier, is a hollow man filled with winding keys and existential dread. Jack Pumpkinhead, while offering moments of pathos, is a gangling construct with mother issues and a decaying head. The Gnome King’s true form – a monstrous, roaring rock beast revealed in a rather startling transformation. The stakes are way higher than just getting home.

What makes Return to Oz truly unsettling is its grotesque imagery and pervasive atmosphere of decay and loss. Walter Murch’s direction crafts a world drained of warmth, where every shadow feels threatening, and the familiar landmarks are twisted into monuments of despair. The Yellow Brick Road is buried, the Scarecrow is imprisoned, the Tin Man is inert. It’s a reflection of Dorothy’s fractured psyche post-Kansas tornado, amplified into a surreal, dangerous purgatory. It presents childhood anxiety – fear of abandonment, medical authority, bodily harm, losing one’s mind – with startlingly grotesque seriousness.

Labelling Return to Oz a children's film is a cruel joke. It’s a bleak, visually audacious descent into horror wearing the skin of a beloved classic, looking at electroshock, decapitation, petrification and existential despair. Decades later, this film remains a uniquely disturbing artefact. Those wheel-hands still clatter in the nightmares of a generation.

Conor Bryce is a designer, author and amateur filmmaker with a lifelong love of cinema. Born in County Down and a Limerick blow-in for nigh-on fifteen years, when he’s not running after his daughter he’s running along the Shannon with a movie podcast in his ears. He’ll happily talk your ear off about why a Krull remake would rock or how the Last of the Mohicans soundtrack changed his life, but you’ll have to catch him first.