In this article, contributor Mick Jordan writes about the upcoming festival celebrating the 67th anniversary of Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo. Vertigo 67: The final reckoning runs from 12th -15th August. Mick catches up with scholar Richard Allen, who will be speaking on “Vertigo, the Woman in White, and Unreliable Narration in Hindi Cinema" at the event. See the full line-up now at www.vertigo67.com.

Vertigo 67: The final reckoning festival is a celebration and exploration of a film now recognised as one of the all-time greats of cinema and as the pinnacle of Alfred Hitchcock’s career. But it wasn’t always so well regarded.

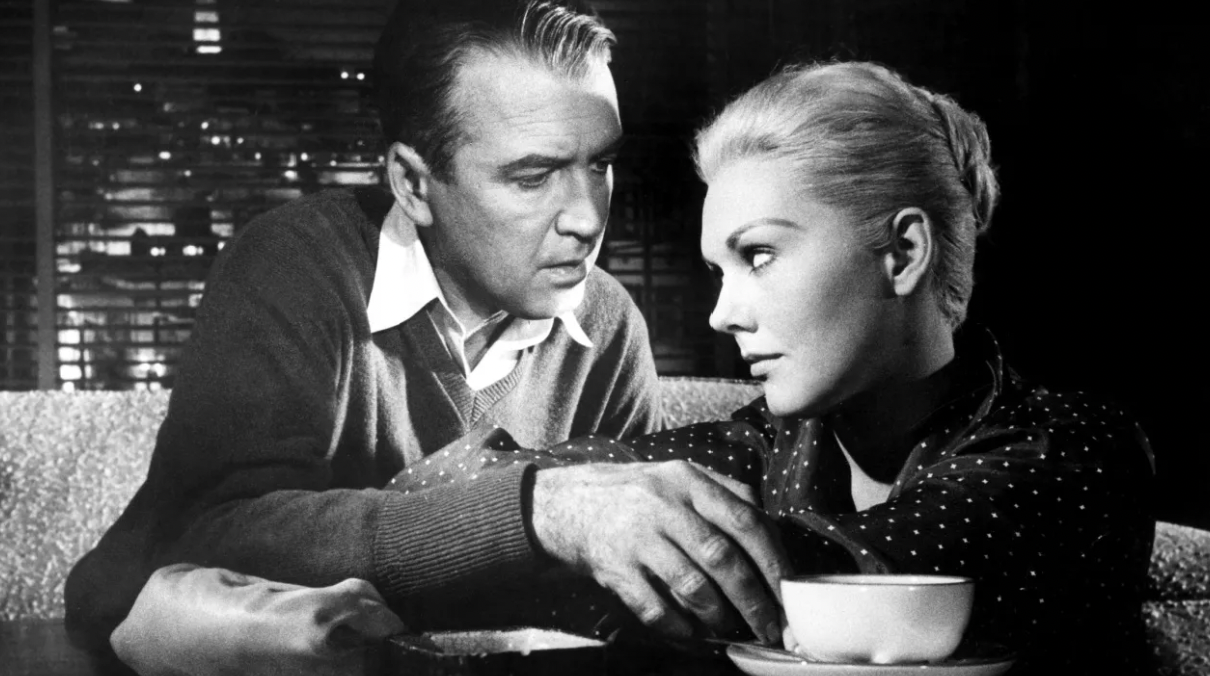

In the 1950s, Alfred Hitchcock was one of the most consistently successful filmmakers at the box office. It was a decade that saw the release of films like Rear Window, To Catch a Thief, The Man Who Knew Too Much and North by Northwest. And right in the middle of them came Vertigo. When the film was released in 1958, audiences were completely perplexed by what they saw. The story seemed at first to be in the classic Hitchcock mould. James Stewart plays Scottie, a former detective who is hired to protect Madeleine (Kim Novak), the suicidal wife of an old friend. He soon falls in love with her - and she with him. When Scottie’s paralysing fear of heights prevents him from saving Madeleine from jumping to her death, he is all but destroyed by guilt and remorse. Then, some years later, he meets Judy, a woman who strongly resembles Madeleine. As their relationship develops, he sets out to remodel her completely in the image of his lost love.

So far, so mysterious - but then, halfway through the film, Hitchcock reveals the twist behind the tale, and audiences wondered what was the point of the story after that. The point was the exploration of one man’s obsession with a ghost and his desperate need to recreate her in another woman. When originally released, Vertigo was not well received by either critics or audiences. They were not ready for such dark themes in a Hitchcock movie, particularly with the casting of wholesome Jimmy Stewart as a sinister obsessive.

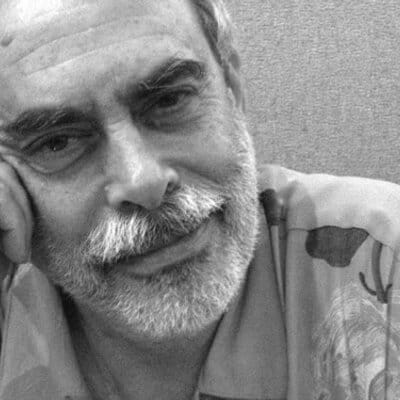

But don't take my word for it, ahead of the festival, I spoke with acclaimed scholar Richard Allen, about his thoughts on the matter. ..

Why do you think Vertigo continues to provoke such strong critical and academic interest 67 years on?

Richard: Vertigo has the timeless quality of fairytale romance, albeit a distinctively modern one. It is about a man’s romantic obsession for a woman, and about a woman, who, seeking to exploit that obsession under the shaping control of another man, falls in love. When he seems to lose her, he remakes a stranger in the image of the woman he has lost and thereby destroys his love in the act of trying to recreate it, for the stranger turns out to be the same woman, and his discovery of her true identity seems to expose his love as a lie. As if this was not enough to provoke critical interest, Hitchcock tells this fairytale utilizing the full resources of what he liked to call “pure cinema”— music, mise-en-scene, colour, cutting, and camera movement without dialogue. By aligning the spectator with the protagonist’s obsession for “Madeleine,” the elusive and fictional ideal of woman is identified in Vertigo with the ideal of cinema itself as a beautiful and compelling illusion, which Hitchcock’s film at once realizes in the perfection of its form, and yet, at the same time, in the famous, jarring, dolly-zoom “Vertigo” shot, destroys. It is thus the ultimate cinephile’s dream.

The film was once seen as a lesser Hitchcock, now it’s considered his masterpiece. What changed?

Richard: For a long time, critical opinion favoured Hitchcock’s English films over his American ones. Vertigo seemed contrived. The French critics, but then above all, Robin Wood, in the 1960s changed all that. Then Vertigo was re-released in the 1980s (it had been withheld from circulation), and audiences saw it with fresh eyes. It appeared as the acme of Hitchcock’s achievement in Hollywood Studio film-making. A movie in which Hitchcock used all the resources of cinema at his disposal to create a film of aching beauty and masterful form, which at the time displays his rather dark vision of the human condition.

How do you think younger audiences respond to Vertigo today compared to earlier generations?

Richard: Hitchcock used to say that films were slices of cake rather than slices of life. I think that modern sensibilities are much more comfortable with slices of cake, films that don’t stake a claim to realism in the everyday sense, and whose stories are contrived. I think the younger audience responds to the cinematic qualities of the film, its aesthetic and its mood of suspenseful mystery, which convey its aching and ultimately debilitating romance. However, I also think that a significant group of young people find Scottie too old and the film too slow!

This year’s festival includes topics as varied as feminist theory, Indian cinema, and Severance (2022). What links them back to Vertigo?

Richard: Vertigo has been a touchstone for feminist theory for decades, since a pioneering essay by Laura Mulvey in the ‘70s. This is because it exposes the coercive nature of male desire. The hero falls in love with an ideal image of woman, manufactured by a man, that is cut to the measure of his desire. When he thinks he has lost her and discovers her look-alike he proceeds to forcibly remake her, re-manufacturing through her body this ideal image has lost. Hitchcock’s Vertigo has also influenced cinema the world over, because of its command of cinematic story telling. In the case of Indian cinema, the figuration of a man who is pursuing a mysterious seductive woman after Vertigo, forms a kind of meme, a recurring pattern, in song picturization of the 1960s and after. On the connection to Severance (2022), I don’t know, you will need to come to the conference to find out!

What do you attribute the sustained interest for discussion on Hitchcock’s Vertigo, from such a wide range of academic and non-academic contributors alike?

Richard: I think this is due to the continuing interest in Vertigo as a kind of “matrix” film that distils such a wide range of themes and influences from Western culture, expresses an ideal of what cinema can achieve, and radiates outwards to inform a multiplicity of film histories. It is also because this kind of conference is very rare on the academic scene, whereas you say, academics and non-academics join together to explore and celebrate cinema.

Thank you, Richard!

Academia and fans of cinema seem to agree... in the years that followed its original release, Vertigo has been dramatically reappraised and is now considered to be Alfred Hitchcock’s masterpiece. Indeed, it has been a constant in the top ten of the British Film Institute’s “Greatest films of all time” poll since 1982. In 2012, it topped the list, replacing Citizen Kane (1941), which had been in residence in the top spot since 1962. In the most recent poll of 2022, Vertigo was ranked in second place, below Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975).

Vertigo is a film that has been the subject of several books, documentaries and many, many film student theses. There is so much to explore in the film, so many different elements that, combined, make this the great film that it is. The Vertigo 67 festival brings together a group of international scholars to present a series of talks and discussions on the film’s lasting power and influence.

This is the fourth such celebration, which began in 2017 as a one-day event with seven guest speakers. It has now expanded to a four-day festival, which kicks off with a special 4K screening of the film at the Lighthouse Cinema on Tuesday 12th August at 8pm. This screening will be introduced by Elizabeth Buckley from Dominican University, Illinois. The festival continues the next day in the Trinity Long Room Hub, Trinity College, and runs until Friday 15th August.

More than 20 presentations, talks, interviews and panel discussions will make up the festival, with international speakers from the US, UK, Hong Kong, Ireland and Switzerland. There will be a wide variety of topics up for discussion, including including discussions on the film's influence on Indian cinema, feminist film theory and cult television series - from Twin Peaks to Severance. The festival also celebrates the huge importance of the film’s soundtrack, and there are a number of presentations on the collaboration between Hitchcock and composer Bernard Herrmann.

Fans of the film will be in safe hands. The artistic director of the festival is Donal Martin (TCD), who has himself co-authored (with Sidney Gottlieb) Haunted by Vertigo (Libbey, 2021), with two further publications scheduled for 2026 and 2027. This is a don't miss event for those with a hunger to learn or obsession with the classic.

Full details of the festival can be found at www.vertigo67.com.

Richard Allen

Richard Allen is Chair Professor of Film and Media Art at the School of Creative Media at City University of Hong Kong. He is the author of Hitchcock's Romantic Irony (Columbia University Press, 2007), which examines the relationship between sexuality and style in Hitchcock’s work. Allen has also written extensively on Hindi cinema, commonly known as Bollywood.

https://filmireland.net/2023/08/04/podcast-murray-pomerance-vertigo-65/

https://filmireland.net/2017/09/13/charles-barr-on-vertigo-the-greatest-film-ever-made/