This week at the IFI, filmmaker and activist Róisín Kearney attended Born That Way, a documentary that hit very close to home. Her personal experience with Camphill, which features very prominently in the film, dates back to 1992. Her brother, Enda, lives at the residential and support community for people with intellectual disabilities. Róisín spoke with filmmaker Éamon Little to learn more about the important subject matter that inspired his documentary.

“Judge oranges by what it means to be an orange, judge apples by what it means to be an apple.”

In an era of Magdalene laundries and Mother and Baby homes, Patrick Lydon and others like him created a community of equals. A place where my brother, a man with an intellectual disability, was a co-worker, valued for what he could do rather than devalued for what he could not.

Born That Way is a beautiful, reflective portrait of a man and his life’s work. But it is also a reflection on how society has changed over the last decade. Patrick, in the documentary, reflects on how people with an intellectual disability are his teachers. Éamon has managed to encapsulate an important lesson for us all in this moving film.

What drove you to want to tell the story of Patrick and Camphill?

ÉL: Like yourself, I had seen Camphill life in action since the early nineties and my family had reaped its fruits. My brother went to live in Camphill Grangemockler, in Co. Tipperary, in 1991. He had been an orphan nine years by the time he found that place. Now he had, for all intents and purposes, a new, larger family. He blossomed. Visiting him often and staying over, I got to see how Camphill life worked on the ground. I met wonderful people committed to the way of life there, with extraordinary attention to detail. My relationship with that community deepened over time. I knew they were part of a wider movement but it was not until the Camphill Communities of Ireland asked me to make a promotional film for them in 2008 that my interest widened out to the other Camphill places.

Making that twenty-minute promotional piece (Camphill – The Essence From Within) introduced me to more people in various residential Camphill communities and social initiatives who lived this alternative way of life with full commitment, flying under the mainstream radar. At what seemed like the centre of it all were Patrick and Gladys Lydon, then living in Camphill Callan. The people and communities that surrounded them seemed happy and healthy and creatively busy. The opening shots of Born That Way (and many others peppered throughout the film) come from that shoot, the first time I ever filmed Patrick. He and I seemed to have a natural affinity and he was very fond of my brother, so it did not take long for us to become friends.

Making that film also brought me to KCAT, the inclusive arts centre in Callan, a space that stayed with me long after I had finished that job. I went back there in 2010 and made the feature documentary Living Colour (Trailer), which brought me to Callan for much of that year. Patrick and Gladys lived then on the top floor of the KCAT building so I often dined with them. A meal at their table was a movie in itself, Patrick simultaneously conducting conversations with four or five different people of different nationalities and intellectual abilities, like a man on a unicycle spinning plates, and taking calls and texts while he was at it. Soon afterwards, my brother moved from Camphill Grangemockler to Camphill Callan. He wanted now to live in a town, so I now had far more than professional reasons to visit often.

Over the following decade I documented on video the evolution of the Nimble Spaces project, with Rosie Lynch, who had grown up in Camphill Ballytobin, and Patrick at its helm. Seeing the writing on the wall for the Camphill way of life in residential communities, the idea here was to see whether the Camphill impulse could be put to work in the area of housing. It was a fascinating process of workshopping with people who would not have the usual skills required to articulate their domestic spatial needs and desires to the usual architect. A board game was even developed to help elicit, from a wide variety of people, the information and understanding needed to design what came to be called an Inclusive Neighbourhood in Callan, where people with and without disabilities would live alongside each other as constructive or supportive neighbours, not carers or service users. Those videos can be seen on Vimeo. During this period I tried to interest RTÉ in commissioning a film about the Camphill way of life in Ireland but they just would not bite. I made this teaser for that effort, which became hugely popular in the Camphill world.

So, by 2021, I had all this material and experience accumulated and when Patrick told me of his terminal diagnosis, the penny just dropped. I needed to make a film about Patrick’s life and work, and quickly, while he was still able to speak. The film about Camphill I had wanted to make would emerge through that. At that point, it was not so much that I wanted to make this film, it felt I had no choice. It was demanding of me that it be made and that I was the one to do it. I knew immediately it should not be an in-praise-of-Patrick hagiography. This was a last chance to take a look at the world and his work in it, through his extraordinary lens.

Your access to Camphill community was extensive and there is a real honesty that comes across throughout the film. What is or was your approach when working with the subjects of the documentary?

ÉL: Honesty in film, I think, means treating the people you are filming for who they are and not trying to make them something else for the purpose of your film. It means getting into their space, their sense of time, their view of the world. It helps when you know them a long time or if you can be at ease with people who then come to trust you. The trust in this project was huge. Patrick knew he would never see the finished film. Often, when I brought up difficulties or anxieties I had about how things might come out, he just said, “I trust you.” On the subject of the illness he told me one day we should “go for the pure drop”, meaning I should not be afraid to get in there and film difficult and intimate moments of his need for care as the illness advanced. I told him I would try to honour that access. He replied, “I trust you.”

Did you know the story you wanted to tell? Or was it a more organic process?

ÉL: In broad strokes, I knew the shape of the film and much of the story, though not in all its details. I knew that there would have to be two timelines running through the film, Patrick’s life story and Patrick’s final year on earth. What would make the cut in either timeline was never sure. There was so much of interest in his life, and so much material from his final year (I worked in Callan 89 days in 2021 alone, according to the recorded files) that it had to all be gathered in and sorted out in the edit. There were quite a few things I thought could not possibly get left out that eventually were, and a few things that sneaked in that were not so obvious to include until near the end of the edit. I also knew that due to the way Patrick spoke and the constraints laid down by the conditions in which I interviewed him, his narration would need a lot of cutting up. There would have to be a huge amount of archive sourced so that it could be refined to the optimum, well illuminated and delivered seamlessly.

Huge credit goes to Keith Walsh who, after shooting some of the best stuff in the film, then tamed the monstrous beast in the edit. We had something like 175 hours of footage, not including archive. Harking back to earlier questions also, Keith, having entered that Camphill world of Patrick’s through the shoot, really got the film at a very deep level and deployed his great gifts on it in a way for which I will be eternally grateful. In a parallel way, I have to say the same for our main producer, Adrian McCarthy of Curious Dog Films, who had produced Living Colour and had been very touched by Patrick and his world way back then.

"Honesty in film means treating people for who they are, not trying to make them something else for the sake of your story."

To document a life as that life comes to its end, particularly someone you have a relationship with, is incredibly difficult. How did you approach this as a filmmaker and friend?

ÉL: I found myself compartmentalising, a trick for which I seem to have a natural talent. Throughout the shoot I tended to switch off my emotional responses when necessary (that is, a lot) as best I could, without being blind to the power of what I was witnessing. Sensitive and careful though one needs to be, one cannot forget one is making a film and the aim is to make the best possible film and one has to always concentrate on picture, sound, what is happening in the frame and what is about to happen. So you park the emotional response until later. Keith said that he had to do likewise while shooting and that it was only when driving home afterwards that the emotion of the situations we had filmed would hit him. In my case, I think I was parking in the long-term lot. I had to keep the emotions at bay until the whole project was over. I also had a lot of other big stuff going on in my life from the end of 2021 that needed immediate processing.

It took quite a while to get the full budget together and all the final footage in the can (we had shoots in Scotland and the US after Patrick died) and throughout that time Patrick seems to have remained alive for me, even more so throughout the edit where he was speaking to us all the time. And now that the film is being screened a fair bit and I have to attend screenings, he is still motoring. I imagine that before too long I will find myself finally putting him to rest in my heart and grieving for him wholesomely. But while we are still on the job, we must park that.

How long was the overall shoot? Did you edit as you went?

ÉL: The main shoot was on and off from April 2021 to Patrick’s funeral in January 2022. And then there were shooting trips to Aberdeen and the US. I edited bits and pieces as we shot so as to make and update a teaser to help us raise the budget. Other than that, I interrogated the interview material on the edit suite to ensure no important stones had been left unturned. The edit itself went from March 2024 to December of that year.

Is there anything you wished you knew before going into this project?

ÉL: Not so much knowledge as skill. I often wished during this project that I was a better camera operator (and had a better camera). I was usually okay for anything that was static (though my eyesight is not the best and focus was sometimes an issue) but when subjects and cameras needed to move I was generally at a loss. Fortunately we got Keith on board by July 2021 and he captured a lot of really great material from when Patrick was still getting around in his wheelchair to his funeral. But I was often in Callan without Keith and was limited in how I could capture what was unfolding. This became one of the constraints of the job but there are always constraints in documentary. Doing your best within them is all you can do.

You work across both drama and documentary. How do you feel they differ or compare?

ÉL: First and foremost films are films, designed to be viewed on a big screen by a tacit and temporary community of people. I am interested in enhancing the viewers’ cinema experience, even more than in the story, whether documentary or drama, though of course the story is usually a major part of that. But you can make a poor cinema experience out of a good story. And you can make a rich cinema experience out of something in which it is hard to put your finger on the story.

I think that is what Pat Collins did with That They May Face the Rising Sun. There we decided to just lose the plot. I love films that blur the lines between documentary and drama like, say, Abbas Kiarostami’s films, so working with Pat on that film was right up my alley. John Grierson defined documentary as “The creative treatment of actuality.” But drama is surely the creative treatment of reality. They are not that far apart.

For me, how documentary and drama mainly differ is not in their end products as much as in the process of making them. I have written and directed short films but have not yet directed a feature. I know from the shorts how much directing a film can take over your life. Documentary can be similar, as it was in this case, but you are dealing with far fewer people and it is possible to hold onto the intimacy at the heart of the project more easily. Even with a low budget drama, wherever you are shooting there are actors and trucks and cars and catering buses and honey wagons and walkie talkies and god knows what all else.

No matter how authentic your script, you are reminded at every turn that the whole thing is a contrivance. Only the director, I think, can hold the whole thing in his mind as a piece of truth until it hits the big screen. Directing documentary is easier on that score. And yet, this particular project took over my life for the guts of four years. Whereas writing drama for someone else to direct seems the easiest option of all. That may not work on all drama projects, however. Some of them cry out to be directed by their writer.

Is there anything you would have liked to explore further, and learnings from the making of the film?

ÉL: I think we explored the subject of Patrick as exhaustively as a film would allow. Yet there are issues of great interest to me, and of importance generally, deliberately only touched on in the film, which were very close to Patrick Lydon’s heart. These concern the rights and treatment of people with disability in this country and what has become of Camphill in particular. I did not want those things to overshadow the film and become what it was about, but I hope that Born That Way deals with them just enough for questions to be raised and serious, possibly public, discussion to be provoked.

Despite the 2007 United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, despite the 1996 report of a government commission of inquiry, established by Mervyn Taylor, recommending that disability support be moved away from the Department of Health to another, more socially orientated department, and despite the fact that we now have a Minister for Disability, disability in Ireland is still officially regarded primarily as a health issue and financial support for people with disabilities comes from the Department of Health. And he who pays the piper calls the tune. The social dimensions of a person’s life do not appear to fall within the remit of the health services though, ironically, they are hugely important to a person’s health.

This is at the bottom of the demise of such a wonderful movement as Camphill in Ireland and why relationship-based care has largely now been professionalised and systematised into a medical model. But as Patrick says in the film about people with disabilities, “Their issues are not health issues. They are who they are.” However, it is not the intention of this film to deliver messages. If delivering messages was my intention I would have looked for work in the postal service. My job was to make as good a film as I could with the material at my disposal, in the belief that if I could do that, any messages inherent in the material would shine through.

The learnings from the making of the film are still accumulating. It might be too soon for me to elaborate on them.

Born That Way is screening at the IFI until Thursday 27th November 2026. Check out their list of local screenings here.

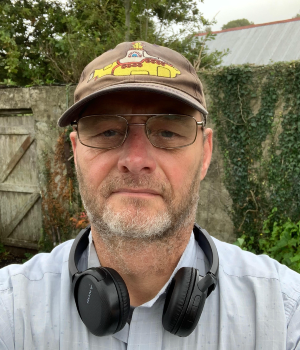

Éamon Little

Éamon's previous feature documentary films include Living Colour (2011), IFTA nominated Red Mist (2007), and An Domhnach in Éireann (2005) which he co-directed. More recently he adapted for screen, with director Pat Collins, John McGahern’s final novel, That They May Face the Rising Sun, which won Best Irish Film at the IFTAs in 2024 and has screened in film festivals all over the world.

He has written and directed three short fiction films: quickfix (1996), Nobody Home (2002) and Neighbourhood Watch (2010) and has a number of other feature film screenplays currently in development. Short documentary films include Camphill - The Essence from Within (2009), Nimble Spaces - An Introduction (2013) and Nimble Spaces - Inclusive Neighbourhoods (2016). For radio he has made a number of what he thinks of as films without visuals, all of which can be heard here LittleVision Radio Works