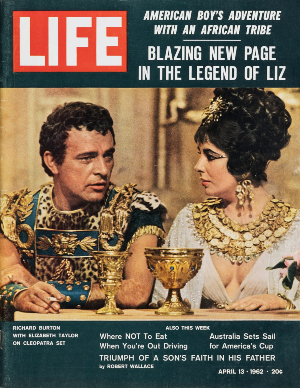

Richard Burton, who would have celebrated his 100th birthday this November had he still been alive, was a celebrated Welsh actor of stage and screen, admired for his commanding voice and his compelling portrayals of sharp-witted, often world-weary characters. This is an excerpt from the latest book by film historian and contributor Aubrey Malone, Poisoned Chalice: How Fame Ruined Richard Bruton.

Public interest in the double act of Richard Burton and Elizabeth that had been fuelling the media for the early sixties started to diminish by the middle years of the decade. The “Dick and Liz Show” was in danger of turning into parody. A writer in Look magazine remarked, “What other young couple would go to such lengths to make home movies for their fans?”

They weren’t that young. Burton was now forty and Taylor 33. The public seemed to be more interested in talking about The Rolling Stones, James Bond, the Vietnam War, Christine Keeler’s recent affair with John Profumo. The “angry young man” phenomenon had begun to infiltrate British cinema with the likes of Tom Courtenay, Alan Bates and Albert Finney, making Burton already seem somewhat passé. As for Taylor, she was looking over her shoulder at new “eye candy” like Julie Christie, whose name was on everyone’s lips after her Oscar turn in Darling.

For Burton it was time to get back to some serious work. This was achieved by what many consider one of his finest ever performances, that of Alec Leamas in Martin Ritt’s adaptation of John Le Carré’s convoluted espionage novel about double agents during the Cold War, The Spy Who Came in From the Cold. It was shot in various places – Dublin, Bavaria and the Netherlands.

He made it in the hope that it would provide an antidote to the plethora of James Bond movies that were appealing to the lowest common denominator of public taste as the time. Ritt underlined its difference to the glossy Connery capers by filming it in black and white.

Burton liked to dress elegantly for films, having a distaste for anything that reminded him of the poverty of his youth. Ritt had to deny him this for Leamas, making him wear a grubby suit and raincoat throughout. This gave us a Burton we weren't used to seeing, someone from the "real" world. Dressing down made him act down as well, something that was also unusual for him.

He may have “Burtonized” Hamlet (and most other roles he undertook?) but Ritt was determined to "Leamasize" his character here. Or even Jenkinize him, Jenkins being the name he was born with, in poverty. For fun he had "Richard Jenkins" written on his set chair instead of “Richard Burton.” He couldn't have made the point more clearly. The superstar was going to be sent back to his home village of Pontrhydyfen — at least in his head.

He wasn't used to working with a director who had different ideas of how scenes should be performed. After doing one to his satisfaction, he was surprised to hear Ritt call for a retake. "It was good enough for me," Burton said, to which Ritt replied, "Well it wasn't for me." For a moment, he thought Burton was going to take a swing at him. Then he cooled down and did it again. This was the moment Ritt set out his stall to Burton. He was the boss.

Claire Bloom was, once again, his co-star. He had cast approval. After three flops with Taylor he thought it was necessary to leave her aside for this. Bloom was surprised he chose her because of the affair they’d had in the past, which ended with him leaving her for Taylor. She knew Taylor was aware of this and would be threatened by her. Maybe Burton was sending out a message to Taylor that she needn't be afraid of his past mistresses any more than she had of people like Sophia Loren or Ava Gardner. She knew that Bloom more than any of his other lovers came closest to taking him away from Sybil.

Burton was Hollywood royalty by the time he got to Ireland. He stayed in the Gresham Hotel on O’Connell Street. Cleopatra was showing in the Savoy cinema just a few doors down from it. He was mobbed everywhere he went. When he was filming, crash barriers had to be erected to keep the crowds away.

Taylor arrived in Dublin one night when he was shooting a scene. She'd got a police escort to the set. There was no more shooting done that night. As ever, her arrival seemed to matter more than the film. In no time at all there were crowds thronging her. Ritt shut up the shop.

Taylor had wanted to be in the film but Ritt knew there was no way she could be convincing as a mousey librarian. Bloom's character was originally called Liz. It was changed to avoid the obvious connection in viewers' minds.

Bloom was now married to Rod Steiger — a man even more mercurial than Burton — but Taylor still watched her like a hawk for any sign of the old romance being re-kindled.

Burton and Taylor rented out a whole floor of the Gresham for the Dublin scenes. By now hotels had become almost like second homes for the couple. The expanded space was necessary for their ever-growing entourage.

Bloom still had strong feelings for Burton. Burton didn't encourage these, telling her that waking up beside Taylor in his bed was like having Christmas every morning. Taylor, however, still felt threatened by her. She'd wanted to play her role but Ritt knew this would have thrown the movie off-kilter, making it into another Burton-Taylor vehicle rather than an intense espionage work that depended on the chemistry of two stars. They’d only been seen once on screen together, whatever about the stage. Taylor made a point of being present when the film was being shot, summoning Burton to her side with a peremptory cry of "Richard!" whenever a take was completed. Bloom thought he was terrified of her.

She accepted the fact that Burton was gone from her forever. Her heart had been broken by him too many times. She once said, "I am allergic to emotion." This was perhaps a protective mechanism she adopted when dealing with men like him. She told people he'd lost his attractiveness for her. That may have been another protective mechanism. "He was still drinking," she said, "He was still boasting, he was still late, he was still reciting the same stories as when he was 23."

Bloom made some of these comments to Sheilah Graham in an interview. Burton's reaction was to say, “I have only four words. Hell hath no fury.”

Leamas, according to Le Carré, was a self-destructive figure. That came across especially in the last scene where he's on the top of the wall and could easily drop to the other side of it. He decides not to do so because Bloom has been shot. He shows a loyalty to her here that he didn't in real life. There's no point in his action. She's dead. Now he will be too in a few moments. His world weariness is never more apparent than in this scene.

He drank a lot while the film was being made. Bloom suspected the "coffees" he had in the mornings weren't just coffees. At noon he gravitated to champagne. Lunch was wine with his cronies by late afternoon he was usually well out of commission.

By now alcohol had taken an effect on his body. When he held her in his arms for an embrace it wasn't the powerful arm she'd remembered from previous collaborations: the muscle tone was gone. It also affected his memory. He often had to have his lines written on cue cards. A scene that occurred towards the end of the film that should have been done in a single take took three nights to complete. 51

There was one scene which called on him to drink a glass of whiskey. Ginger ale was given to him instead, the usual practice in situations like this. "It's only a short scene," he said, "Bring me some real whiskey." The scene had to be shot 47 times before he got it right. Just this once he didn't complain. He was too drunk to.

Burton was brilliant in the part. Ritt stopped him relying on his customary orating to give a tense, downbeat performance. "I needed him to be sick and tired," he said, "He wanted me to let him loose but I held onto the reins." Kenneth Tynan wrote: "His dour and expressively ravaged face comes to resemble a bullet-chipped wall against which many executions have taken place." Leonard Mosley wrote in the Daily Express, "His performance makes you forgive him for every bad part he has ever played." He earned an Oscar nomination for it.

Lee Marvin won that year for Cat Ballou. Burton grumbled, "Are they trying to tell me he was a better class of drunk?" Neither man, it should be added, would have had to do much acting for such roles.

Bloom was excellent in the film too, conveying a tension and timidity that wonderfully offset Burton's ravaged brokenness. Both of them looked distinctly uncomfortable in their roles for reasons that went way beyond the plot but enhanced it no end.

The shoot wasn't a happy one for all sorts of reasons. Burton’s adopted daughter Maria caught the measles during it. That wouldn't have been a worry with any of the other children but with her it was because of other medical problems she had. Then the son of their chauffeur, Gaston Sanz, was killed in a shooting accident in Paris. Taylor flew over for the funeral. While she was there, some jewellery worth $50,000 was stolen from her room in the Gresham. Upon her return to Dublin, Sanz killed a pedestrian in his Rolls-Royce. Then Taylor's father suffered a stroke. She flew to Los Angeles to be by his side. Taylor was afterwards hospitalised herself with gynaecological problems and the reoccurrence of a back injury.

Burton hated being trapped in the hotel while the film was being shot. He feared being mobbed if he left it — not so much because of himself as Taylor. "She's more famous than the Queen," he bragged.

Bloom only saw Burton and Taylor socially once during their time in Dublin. It was on a night that Le Carré was visiting the city. Both he and Bloom joined the pair in their suite. The evening began well, with Burton and Le Carré trading anecdotes. Bloom enjoyed them but Taylor was in poor form. It wasn't her style not to be the centre of attention. After an hour or so she went up to her bedroom in a sulk, thereafter summoning Burton every few minutes to join her. She conveyed these messages through a speaker system that connected the bedroom to the suite. Burton was enjoying himself too much to "obey" them. After a while Taylor re-appeared, as Bloom put it, "like some spirit of vengeance." Thereafter a shouting match developed between them.

Burton excels particularly in the last scene of the film. He sits ruminating on top of the Berlin Wall – recreated in Dublin’s vast Smithfield area – wondering whether to jump to freedom or go back to Bloom. She’s just been shot by the Germans trying to escape.

Maybe we could take it as a metaphor for the conflict in his actual life. Would he choose freedom or loyalty? In the film he opts for loyalty. The real life Burton deserted Bloom. Great acting?

He’d take the compliment even if it was a left-handed one in the circumstances.

Poisoned Chalice: How Fame Ruined Richard Bruton will be available to buy in bookshops shortly.

Aubrey Malone has an MA in English and was a primary school teacher before he then went into journalism, freelancing for publications including the Evening Press, The Cork Examiner and the Sunday Independent. He was the movie critic for Image magazine and for Modern Woman, a supplement to the Meath Chronicle. His books are available to buy online now, including Hollywood Wit, MYSTICAL CROONER: The Lives of Leonard Cohen, and Michael Collins : [a Neil Jordan film].