Naemi Victoria cracks open the spine of Queer Horror: A Film Guide.

“It is the spectator, and not life, that art really mirrors,” Oscar Wilde declares in the preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891). First published in 1890, the novel sparked furious controversy because of its alleged moral depravity. Wilde responded to outraged critics in a later edition by suggesting that their condemning reaction revealed far more about their own narrow-mindedness than the subject of their scrutiny. In the century that followed, the reception of The Picture of Dorian Gray changed quite significantly. Nowadays a celebrated part of the Western literary canon, the novel invites queer readings of its characters and the homoerotic undertones of their relationships. It also illuminates the timeless thrill of stories that confront our fear of mortality. Similarly to the painting in question, fictions of darker subject matter present fertile ground for interrogating society’s norms and moral anxieties.

In the cinematic landscape, no other genre seems to polarise as much as horror. If art does in fact mirror the spectator, as Wilde claims, then cinema must be the reflective surface we see ourselves in.

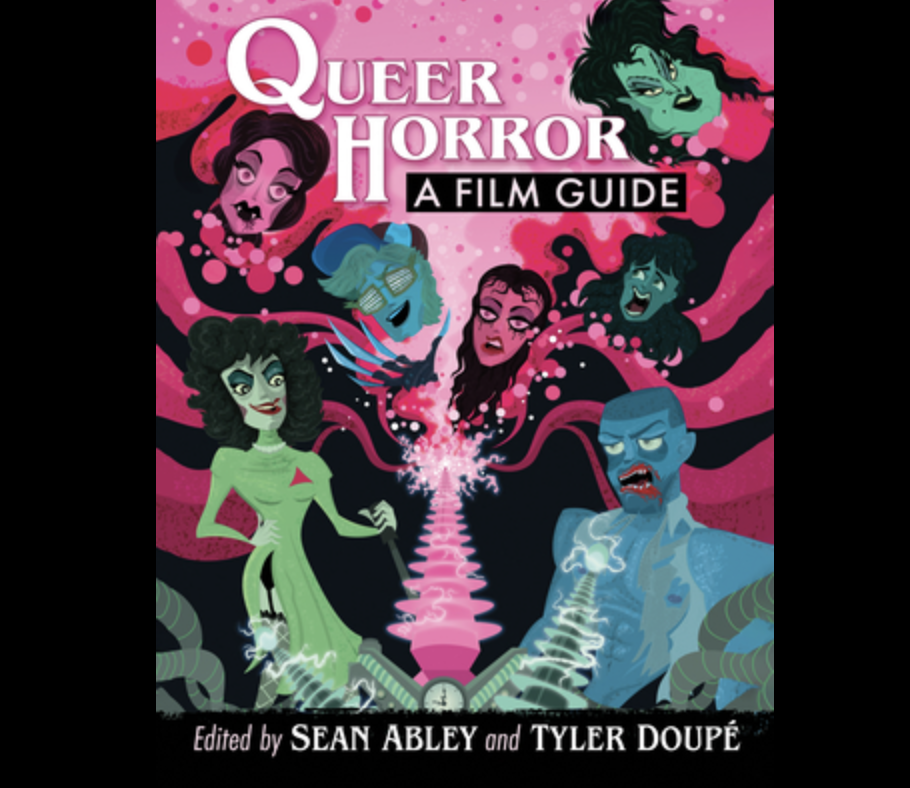

Sean Abley and Tyler Doupé’s Queer Horror: A Film Guide situates itself at the intersection of horror films and queer representation to carefully inspect the image on the silver screen that gazes back at the spectator. Organised alphabetically, the book lives up to its title and guides readers through over 900 bite-sized reviews which, among other things, cover a lavish abundance of punning titles like The Walking Drag (2014). Spilling the guts on over a century of cinema history, it voyages from Hollywood’s Golden Era to celebrated classics like The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) and lifts the veil from a rich variety of subgenres. Horror fans of all tastes will likely run the risk of infinitely expanding their watchlists. On top of the over 400 pages of commentary, the appendix supplies a list of films that did not make the cut. All this is garnished with additional resources for queer horror content.

Queer Horror: A Film Guide is brought to life by eight journalists whose personal experiences as avid horror fans and members of the queer community offer compelling insights into the filmic realm of the uncanny. The encyclopaedia promises “very opinionated” commentary and largely meets this expectation. Varying in length and depth, the reviews serve different degrees of critical engagement. Some provide pointers along the lines of “if you’re into this, go check this out,” while others sink their teeth into the gory details. Most entries consist of a brief plot summary, followed by a discussion of queer elements which does not shy away from celebrating and critiquing their ups and downs. Editor Sean Abley, who supplied the vast majority of reviews, provides a constant within the book. His apt observations and humour shed light on LGBTQIA+ content in genre films.

In his introduction to the encyclopaedia, Abley notes that progress towards a resonant depiction of queer experience in visual culture is far from linear. The book’s rejection of chronology hints at that. Travelling back and forth in time, we learn that compelling queer protagonists sit side by side with problematic tropes and violent endings such as that of the gay couple in IT: Chapter II (2019). Viewing each film as a product of its sociohistorical context, the film journalists reveal how cinema chronicles society’s attitudes towards specific social groups and lay bare the demonisation of queer characters in the horror genre. The asymmetry between telling stories about queer experience and telling stories for those living it is a central tenet of their writing. Where the horror genre turned a blind eye to its queer audience, Queer Horror: A Film Guide places prejudices on the dissecting table for closer inspection.

One of the earliest chillers included in the book emerged at a time when queerness was a spectral presence in cultural production. Following the more explorational zeitgeist of the Roaring Twenties, conservative critics in the 1930s feared that the mass appeal of cinema would corrupt the morals of unsuspecting moviegoers. As if the past was bleeding into the present, they seemed to be on the same page as the literary critics of Wilde’s writing in 1890. Commonly known as the “Hays Code,” after Hollywood’s film censor Will H. Hays (1879–1957), conservative voices imposed a strict set of guidelines on film productions to maintain “the correct standards of life.” ‘Correct,’ in this context, mostly meant white, middle-class, and heteronormative. Among other things, the code demanded that the institution of marriage must always be shown in a positive light and other forms of partnership in an undesirable one, or simply not at all. While homosexuality was not explicitly mentioned, it was very much implied and exorcised from Hollywood screens… or was it? Queer Horror: A Film Guide suggests otherwise.

Already in the years prior to the conservative backlash that delivered the Hays Code in 1934, queer elements were carefully embedded in filmic subtext, waiting to be decoded by spectators with the relevant perceptive faculties. Molly Henery’s review of James Whale’s The Old Dark House (1932) skilfully stitches together a succinct plot summary with a careful examination of the film’s queer-coded characters, particularly those of the Femm family. She applies her keen eye to their nonconformity to nuclear family constellations and examines the queer undertones in Rebecca Femm’s obsession with a female visitor. In its brevity, Henery’s commentary lights up the historical context in which Whale, an openly gay filmmaker at a time when this was almost unheard of, pioneered the horror genre with titles like Frankenstein (1931) and The Invisible Man (1933).

If art mirrors the spectator, it must also mirror the artist. With an increased presence of queer artists in front of the camera and behind it, queer representation is continuously evolving and reinventing itself. Where queer characters once occupied the sidelines, they now occupy the very heart of their narratives. Queer Horror: A Film Guide directs readers to these films and welcomes them to a community of horror fans who share their delight in a good fright. Above all, the encyclopaedia is a celebration of queer horror and illustrates that queerness has always been part of horror’s connective tissue, from a silhouette in your peripheral vision to the dead centre of the action.