In anticipation of the release of Testimony today and reviewing Margo Harkin’s Stolen, Seán Patrick Donlan looks at the portrayal of Irish institutions in film.

‘The horrors of the recent past are oozing to the surface’

- Margo Harkin, Stolen (2023)

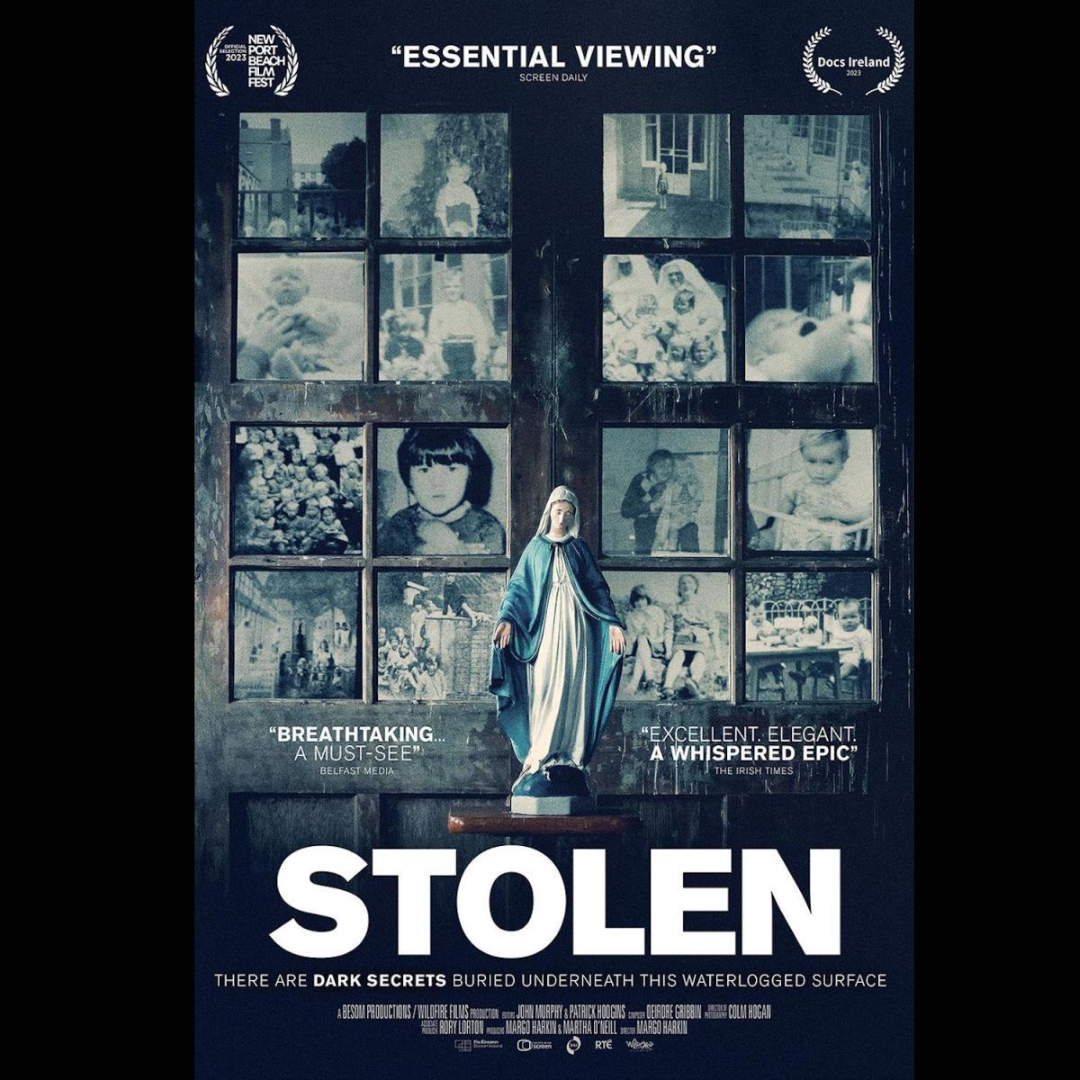

Margo Harkin’s Stolen (2023) begins with, and revolves around, the 2014 discovery of the bodies of almost 800 children at the former site of the St Mary’s Mother and Baby Home in Tuam. As her opening voiceover to the film notes, ‘The horrors of the recent past are oozing to the surface.’

Stolen joins other films, on large and small screens, that wrestle with different aspects of Ireland’s institutional care and confinement. This week, Aoife Kelleher’s Testimony (2025) joins the fight to ensure state recognition of, and redress for, the significant abuses of those institutions.

In Stolen, Harkin asked ‘What happened and why?’ If we’re still learning more about what happened, thanks in part to her efforts, the why question remains more challenging.

Care and Confinement

For much of the last hundred years, the Irish state maintained an elaborate network of institutions of nominal care and quasi-carceral confinement. This was often an insult added to a variety of social injuries: poverty, neglect, and physical and sexual abuse. It included not only prisons but industrial schools for troubled, abandoned, or orphaned youth, Magdalene Laundries and mother-and-child homes, and mental asylums. Indeed, institutionalisation was the default Irish solution to Irish problems. Thousands passed through their cloistered halls.

Of course, similar institutions have long existed across the globe for social and political deviancy. Their targets are often others socially marginalized by class, gender, sexuality, religion, race, and ethnicity. Such institutions have long existed here. The fictional events of Strumpet City (1980), set immediately before the 1916 Rising, centred on urban poverty, the repression of labour, and the harshness of Ireland’s institutions, each without reflexively attributing these ills to British rule. Through its church and state, Irish society across the twentieth century confined those whose suffering challenged its self-image: the poor and orphaned, the sexually and socially transgressive, unwed mothers and their illegitimate babies, and those suffering mental illness.

‘As a society, for many years we failed you./We forgot you or, if we thought of you at all, we did so in untrue and offensive stereotypes./This is a national shame, for which I again say, I am deeply sorry and offer my full and heartfelt apologies.’

- Taoiseach Enda Kenny (19 February 2013)

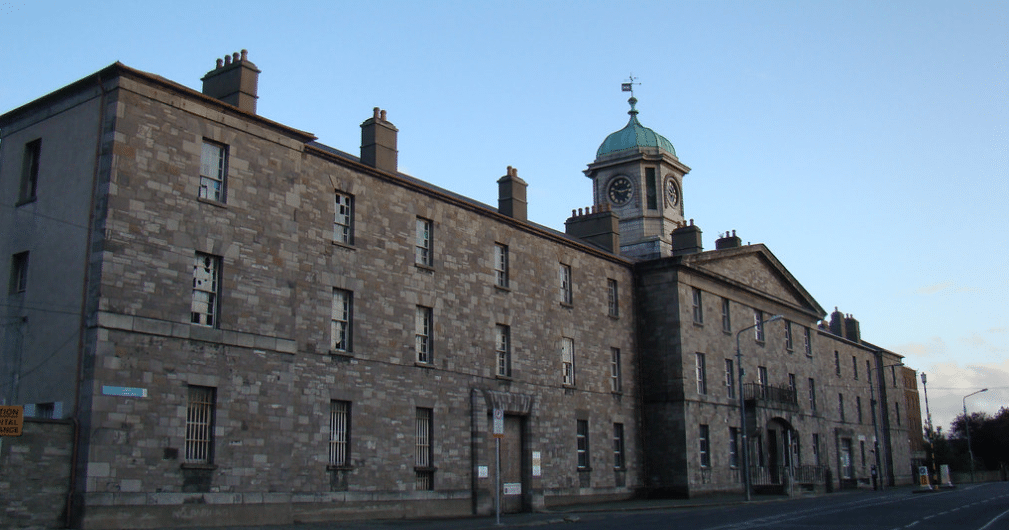

Given its importance to Irish identity, the catholic church was an obvious agent for institutional care in the past. It’s also the understandable focus of present critiques. A century ago, its clergy and infrastructure provided the fledgling state important practical means to its asserted ends. Even where well-intended, such concentrated power, often without active state oversight, almost guaranteed institutional abuse. But the Irish mania for institutions went beyond its entanglement with the church. As Brendan Kelly has noted, especially in Asylum: Inside Grangegorman (2023), mental asylums were state-run and more individuals were committed to their care than all other Irish institutions combined. At the highest rates in the world. Ireland was infused with institutions.

Demands for church accountability still too often fall on deaf ears. But such claims have sometimes served to deflect from acknowledgement of state and public collusion. James M Smith wrote twenty years ago that

Ironically, because Ireland's Magdalen laundries exist in the public mind at the level of story (survivor testimony and cultural representation) rather than history (archival records and documentation) the religious orders, not the State or the Irish public, remain at the centre of national and international opprobrium.*

More recently, in The Best Catholics in the World (2021), Derek Scally’s noted that the public ‘reserve for [clergy] a collective blame that it doesn’t seem to occur to us to apply to ourselves as a people.’** He’s suggested that whatever the direct guilt of contemporary Ireland, there remains a responsibility to truth and public penance, in the hope of state redress and social reconciliation.

Irish screen engagement with the issues of institutionalization developed slowly. For decades, this reflected the significant practical limitations of domestic television and film production. But social critique was inhibited, too, by the pervasiveness of the institutional culture. If much of our past is foreign to our present country, their evils were widespread. They often appeared banal. And they enveloped not only church and state but much of Irish society, including families committing their young, men fathering children out of wedlock, and employers engaging with the laundries.

Magdalens and Mercies

The industrial schools appeared on television with A Week in the Life of Martin Cluxton (1971), a little-seen classic of Irish social realism. Its fictional clergy provide commentary to the film, making it feel like a lost episode of Radharc (1962-1996), the long-running priest-led documentary series. Here, they’re well-meaning and acknowledge their inadequacies for their role, as part of a wider failure of Irish social policy. Martin returns to an overcrowded home, inattentive parents, class prejudice, few opportunities, and all-too-frequent monologues on law and order and property.

Important, too, were Cathal Black’s Our Boys (1980) and Bob Quinn’s Budawanny (1987) and, later, The Bishop’s Story (1994). Each was focused, often with considerable nuance, on abuses in the schools. But a number of documentaries in the 1990s, coinciding with public revelations of clerical abuse and impropriety, would have an even greater effect on bringing such issues to the surface. Louis Lentin’s Dear Daughter (1996), Love in a Cold Climate (1998), and States of Fear (1999) each made ongoing church abuse and state neglect impossible to ignore. State apologies and investigations followed.

Neil Jordan’s The Butcher Boy (1997), adapted from a Pat McCabe novel (1992), was also important, as a narrative film engaging with institutional abuses. As with Bob Quinn’s seminal Poitín (1978) two decades earlier, as well as a number of other films of the 1990s, The Butcher Boy confronted audiences with numerous social and state shortcomings. A victim of generational institutional traumas and neglect, young Francie is sent, in turn, to an industrial school, a mental asylum, and a prison for the criminally insane. The book and film highlight a culture of collusion, of restraint and repentance rather than rehabilitation and respect.

Francie: You have no son. You put me in a home like her [his mother]. What did I do? What did I do?

Da: I loved you like no father ever loved a son, Francie.

Narrator (the older Francie, in voiceover): It was hard for him to say it. I could barely hear him. It would have been better if he drew out and hit me.

Cinematic engagements of the early twenty-first century have been far broader and often blunter. Peter Mullan’s The Magdalene Sisters (2002) and Aisling Walsh’s Sinners (2002) and Song for a Raggy Boy (2003) illustrated institutional abuses of the past, of the 1930s and 1950s. Intended as critique, each went inside Irish institutions to bear witness to the suffering there. Collectively, they suggest vulgar misogyny, sexual shame, and physical abuse. But they largely limit responsibility to the church. Except to introduce students and penitents, we see little of their families, fathers, state officials, or employers. We hear too little of their silence.

Subsequent films were more diverse and indirect. Most closely connected to the films of the previous decade, Philomena (2013) follows the search for a child forcibly separated from its mother and placed for adoption abroad. Less directly, Jim Sheridan’s The Secret Scripture (2016) touches on mental institutions, with considerable liberties taken towards its literary source and the historical past. Frank Berry’s Michael Inside (2017) looked at the cycle of crime, drugs, and incarceration. If this isn’t an entirely novel observation, our most consistently realistic and socially-conscious filmmaker rooted the film securely in its time and place. It speaks to us, now.

More recently, Small Things Like These (2024), based on Claire Keegan’s novella (2021), presents one individual’s response to institutional evils. Like Colm Bairéad’s excellent An Cailín Ciuín (The Quiet Girl, 2022), also adapted from Keegan, Small Things Like These is one of a number of recent films that engage with 1980s Ireland, from various perspectives. Both book and film note the promise of The Proclamation of the Irish Republic (1916) to ‘cherish[] all of the children of the nation equally.’ But despite this theme, Small Things Like These arguably amounts to handwashing, assigning sole responsibility to a caricatured clergy and allowing its lead to act only on the basis of his very specific background. Families and fathers, state and society, may appear absolved.

What Happened and Why?

Margo Harkin has been one of our most important filmmakers for over three decades. Perhaps her best-known work is Hush-a-Bye Baby (1990). Set in her native Derry – she’s from a large catholic family there – in the 1980s, the film doesn’t focus on any physical institution but is a deeply empathetic look at the island’s social institutions or practices, particularly around female sexuality and pregnancy. Most of Harkin’s films have, however, been documentaries focused on the North: Bloody Sunday, the hunger strikes, theatre, mixed marriages, Northern reconciliation, and more.

Stolen appeared in a tsunami of documentaries on Irish institutional abuse, especially involving women and children. It overlaps in different ways with Ireland’s Mother and Baby Scandal (2020), The Missing Children (2021), and Pray for Us Sinners (2022). Among the best of this wave, Ireland’s Dirty Laundry (2022), from veteran writer-director Gerry Gregg, gives religious a voice and probes state responsibility, past and present, more aggressively. More indirect is Alan Gilsenan’s fine The Days of Trees (2023). Humbling and healing, in gorgeous, graceful black-and-white, it centres on Tomás Hardiman, a Tuam native and victim of clerical abuse.

With Tuam as its touchstone, Stolen speaks to victims of institutional neglect, violence, and continuing trauma: Colleen Anderson, Marie Arbuckle, Noelle Brown, Terri Harrison, Adele Johnston, Joanne Neary, and Michael O’Flaherty. It raises questions about the care provided across the island, about state oversight and redress, and about public awareness. The high death rate within institutions, forced admissions and fostering and adoption, and involuntary vaccine trials are difficult for contemporary audiences to comprehend. To Harkin’s credit, among these obscenities, we also see flashes of compassion and the sometimes-astonishing resilience of their victims.

‘Cherish the men/because they couldn’t help it/if the women and girls went and fell pregnant …’

- Sarah Clancy’s ‘Cherishing for Beginners’

In addition to the occasional appearance of the director and an ironic use of Marian images throughout Stolen – already familiar to viewers of Hush-a-Bye Baby – Harkin adds two elements that are less common in contemporary, critical documentaries. She includes an impressive cast of academics, activists, journalists, and politicians: Sarah-Anne Buckley, Catherine Corless, Catriona Crowe, Máiréad Enright, Conall Ó Fátharta, Alison O’Reilly, and Phil Scraton. Each provide invaluable context. Stolen also includes artists, especially poets, to amplify its themes: Sarah Clancy, Elaine Feeney, Rita Ann Higgins, Caelainn Hogan, Annemarie Ní Churreáin, and Jessica Traynor.

Harkin’s Stolen is a worthy contribution to the growing record of truth required for public penance, state redress, and social reconciliation. As a result of it, we know more about what happened, at Tuam and across the island. Why ‘what happened’ happened remains more elusive: a comprehensive social history of Irish institutions remains to be written. Or filmed. To her credit, Harkin’s aims in Stolen are more immediate. As the film moves to its end and its concluding title cards, her critique shifts from church to state, to an acknowledgement of public responsibility and compensation for its victims.

The Institutions of the National Life

Article 45 of the Constitution (Bunreacht na hÉireann, 1937) includes the so-called ‘Directive Principles of Social Policy’. These are aspirational guidelines for governmental and legislative action, unenforceable by the courts or any president. Its first section asserts that

The State shall strive to promote the welfare of the whole people by securing and protecting as effectively as it may a social order in which justice and charity shall inform all of the institutions of the national life.

It’s difficult to read these words without sadness for the past sins of our fathers: in the church, in the state, and in the wider society. They might remind us, too, of the future costs, individually and socially, of our own present failures to ensure justice and charity for all.

Many of Harkin’s films, including Stolen (2023) were screened in September at the Irish Film Institute (IFI), as part of a Margo Harkin: Radical Witness programme.

More of her works are currently available on the IFI@Home and IFI International sites or the IFI Archive Player.

Testimony (2025) is in cinemas from 21 November 2025.

* 'Irish society colluded in betrayal of Magdalen women' (1 September 2003) Irish Times.

**The Best Catholics in the World (2021), 184.