Mutale Kampuni goes on a journey with Frank Sweeney’s experimental short film Go Ye Afar, available to view now in Temple Bar Gallery + Studios.

Myth, fable, folklore, make-believe, imagination, dreaming (lucid or vivid)? It is left to the viewer to decide as they embark on the journey with the Nigerian taxi driver who has made Ireland his home. Bearing testament to the histories of two different cultures with religion as a common denominator. Past norms dictated that the Irish were the ones who had to go afar to other lands to spread their message of the gospel.

In later years, Ireland became the receiving nation for migrants who sought more than just religion, while still having that aspect in mind as they came to ride on the bandwagon of the economic boom. The viewer sees differences and as much distance as is physically possible between continents, but so many similarities too. Perhaps the usual taxi driver and passenger conversations you hear when travelling around any city destination.

In keeping with the themes of the period in which the film is set (2010), there is talk of a nation's financial woes and indebtedness to the IMF. This time it is a European nation that is having to bow to the structural adjustment programme for repaying loans incurred during a financial crisis.

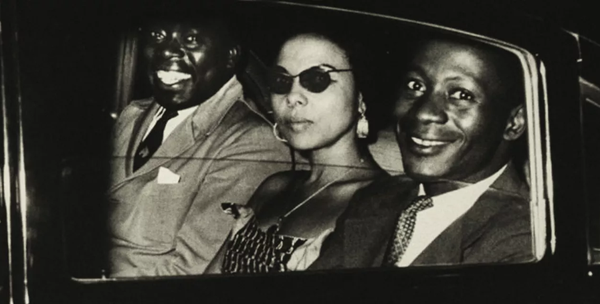

Weaving between, in, around and about, reliving the journeys of the missionaries and their desire to liberate the African through education and religion. Support was also provided to alleviate the effects of a humanitarian disaster precipitated by war (Nigerian/Biafran war 1967–68). Using archival material, facts are recollected and recounted. Supplies were donated by the people of Ireland, the first group to respond when they learnt through media sources the extent of the disaster, in spite of authorities in the recipient countries' attempts to keep a tight lid on things because they could not be seen to be failing to look after their own.

Politics and religion are, as often expected, inextricably linked. The taxi driver's response to the efforts of the do-gooders and post-colonial NGOs: “I still have to change channels when I see those ads.” Though admitting he does still keep a bit of faith, but not religiously, he displays The Motorist’s Prayer in the cab. There is talk of liberation theology in South America and conflict with governments there that perceived a loss of power and its hold over their people once they were enlightened.

Driving over uncertain borders, the driver and passenger alike are unsure as to whether they are asleep, awake or if they are in a virtual reality state. Traffic jams, change of scenery, all in a day’s work. Protests happen on this side and that side for myriad struggles and causes. Against the atrocities of Shell Oil in Nigeria. Different causes in Ireland, the Rossport 5, and Electronic Harassment.

Blending the real and the surreal world, causing one to wonder if there is a meaning to this, or are we all in the same daze. The style used by Frank Sweeney in Go Ye Afar is evocative of Ben Okri’s work in The Famished Road (1991). The taxi is a juxtaposition of reality and symbolism. Historically recorded facts, archival material, documentary, fiction, make-believe, special effects, and it is all thrown in the mix and taken to the next level. Future first, back to the past, always in motion.

The Road to Nowhere comes to mind too, as there is an element of unfinished business at the end. The allure is also in the experience of the not-so-usual set-up of the screening. You are a part of each ride as you sit on bus seats to experience the undulating views, winding roads and pathways to whatever the mind can conjure up.

Go Ye Afar is available to view from 3rd October to 23rd November 2025, in Temple Bar Gallery + Studios Exhibitions.