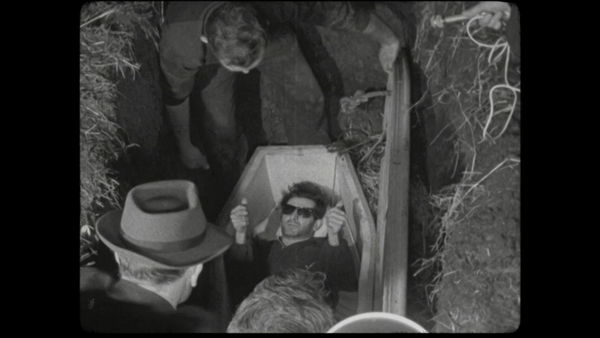

Conor Bryce holds court for Red Rooms.

Stop me if you’ve heard it before – a socially awkward young loner gets progressively more enthralled with the grisly crimes of a serial killer. Sound familiar? Of course it does; from Zodiac to Longlegs, countless entries in the serial killer subgenre follow this tried-and-tested approach. And while French-language Canadian horror Red Rooms shares this common DNA, it’s a wholly different beast. Rich, haunting and provocative, it's easy to see why it's quickly gaining cult classic status.

Red Rooms follows Kelly-Anne (Juliette Gariépy), a successful fashion model attending the high-profile courtroom trial of alleged serial killer Ludovic Chevalier (Maxwell McCabe-Lokos), accused of kidnapping, torturing and murdering three young girls. These horrific acts are recorded and broadcast from a “red room”, a place on the darkest part of the internet where depravity is streamed live and watched in exchange for Bitcoin payment.

Kelly-Anne’s life outside the courtroom is stark and isolated, characterised by late nights spent playing thrill-seeking, high-stakes internet poker, and brief interactions with her agent. Independently wealthy, she still chooses to camp overnight outside the courthouse, eager for a front-row seat to the spectacle, her motivations shrouded in ambiguity. She befriends Clémentine (Laurie Babin), another courtroom regular and self-professed ‘serial killer groupie’. Kelly-Anne’s behaviour turns increasingly erratic as both the trial and her friendship with Clémentine progress: cyberstalking the mother of one of Chevalier’s victims, obtaining and watching the red room footage. Her descent culminates in a climactic confrontation and a final act that is deliberately, deliciously ambiguous.

Emotionally invested in the case, devoutly believing in Chevalier’s innocence, Clémentine ultimately serves as Kelly-Anne’s foil, questioning her ability to remain, initially at least, inscrutable and dispassionate. This dual exploration of true crime voyeurism is where Red Rooms soars – while Clémentine’s blind devotion to the accused raises questions about empathy and complicity, Kelly-Anne’s apparent inability to flinch highlights the fine line between rapt interest and moral depravity.

Writer-director Pascal Plante’s trump card is his disinterest in the visual, visceral gore usually associated with the serial killer subgenre. The courtroom scenes are crafted with a dispassionate lens; a ponderous, Kubrickian camera sweeping ghostlike around the room, capturing an audience enthralled by the gruesome details of the crimes. Virtually bloodless, Red Rooms never clearly shows the horrific acts. Instead, Plante focuses on graphic sounds over graphic visuals, further reinforcing the idea that tragedy can be packaged and presented in a way that distances the audience from its reality. There’s a single short, out-of-focus shot of one of the murders, and the only “death” is of an appliance: an Alexa-like AI voice assistant meeting its grisly end in a blender in one uncharacteristically funny scene.

This prioritisation of suggestion over showing is not a new trick – Jaws, for one, put it to legendarily good use – but it’s an effective one. In Plante’s own words, “if you conjure up gruesome images in your mind, it’s much harder for you to do away with them”. There lies the constant, disquieting feeling that the safety of Kelly-Anne’s sterile life will be interrupted with a sudden rush of blood from a prone throat, but this “release” never comes. This discomfort gives Red Rooms an elegant and gripping terror, without the need or distraction of explicit violence.

The use of a muted colour palette – predominantly greys and blues – adds to this emotionally cold, safely detached environment. Plante also takes a page from Jonathan Demme’s book; similar to The Silence of the Lambs, the camera employs tight, lingering close-ups on characters to give the impression that we’re attending the trial, willing or not.

Relative newcomer Gariépy is Red Rooms’ MVP. Genuinely unsettling, doing so much while saying so little, she navigates Kelly-Anne’s chilling detachment and later moments of vulnerability with a quiet, inscrutable calm that somehow manages to keep us guessing her motives to the bitter end. Similarly, Maxwell McCabe-Lokos as the alleged killer nicknamed “The Demon of Rosemont” is memorable without need of theatrics, chilling in his nonchalance. One fourth-wall-breaking scene where he subtly acknowledges Kelly-Anne will linger long after the credits roll.

Further exquisite oddities lie within Red Rooms’ score. Composer Dominique Plante opts for a fussy baroque that wouldn’t be out of place in a Merchant Ivory offering. It’s akin to the bombastic melodrama of Fargo’s main theme: jarringly paradoxical, at odds with Vincent Biron’s decidedly unfussy cinematography (itself a relative stranger in the subgenre – not since Michael Mann’s Manhunter has a serial killer movie looked so… well, clean). It’s a bold choice, but one that pays off.

Red Rooms is not without flaws. Stereotypical tropes may grate on subgenre veterans – Gariépy’s Kelly-Anne is that all-too-familiar beautiful genius, with an almost supernatural gift for finding things out using nothing but a laptop and a hunch, conveniently advancing the plot. Similarly, Laurie Babin’s Clémentine is often reduced to a stray puppy: naïve, wide-eyed, her unwavering belief in the killer’s innocence teetering close to pastiche. Thankfully, those who can forgive the odd cliché and a leisurely pace (it clocks in at just under two hours) will be rewarded in spades.

Red Rooms is a chilling examination of how our fascination with darkness can lead to desensitisation and moral ambiguity. This is not just a film about a serial killer. Neither is it just a cautionary tale about the dark web. This is a profound commentary on our relationship with violence, and society’s obsession with violence – why we’re, as Plante himself puts it, “a bit bloodthirsty in the entertainment we seek”. It’s a rewarding stare into life’s shadows that might make you think twice about binge-listening to that latest true crime podcast.

Red Rooms is available to rent on IFI@Home.