‘Alfredo. You can start.’ In Cinema Paradiso (1989), a fictional Italian film director reflects on his youth in a Sicilian village, in the years after the Second World War. Before films were shown locally, Father Adelfio viewed them, bell in hand. When there were scenes he considered offensive – usually mere kissing – he rang the bell excitedly, with an occasional cry of ‘No!’. This alerted Alfredo, the projectionist, to mark the movie for cuts. These bits of film, hidden from the villagers, become an important plot element.

Those entrusted to censor films in Ireland over the last century weren’t, in fact, priests. Not quite. But they were a select, frequently moralistic elite: there were only nine Film Censors in total from 1923-2008. And they were, not surprisingly, all men who both banned and cut films, often aggressively. In the Opinion of the Censor (2025) tells this rich and fascinating story of film censorship in Ireland, explicitly discussing those things the Censors had believed best kept from an impressionable Irish public.

In the Opinion of the Censor

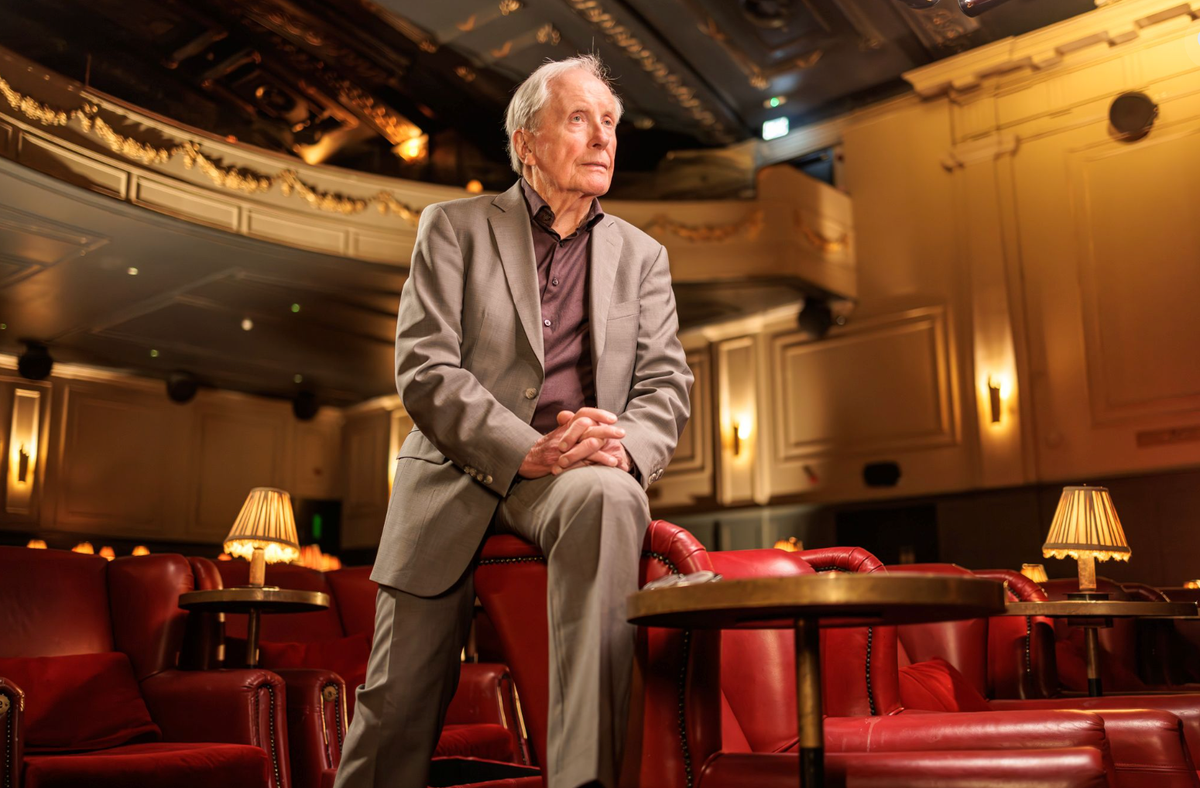

In telling its story, In the Opinion of the Censor is lovely to look at. There are occasional images of the Oireachtas, the source of the 1923 legislation. However most of those interviewed for the documentary speak from the beautiful Stella Cinema Rathmines. That cinema opened the same year in which the legislation was enacted and was lovingly restored only a decade ago. Now, with amendments, this legislation still governs film in Ireland.

Given the past emphasis on banning and cutting films, much of the documentary presents the famous and forgotten, virtuous and violent films of the past. These were the movies and scenes once hidden from public view by the Censors. The editing and integration of these excerpts with expert commentary is deftly handled and compelling. Even in interviews, movies previously censored run in the background in the Stella, illustrating the opinions of the film’s guests.

The documentary’s greatest strength is this expertise, which is elevated by the extensive archival material, including the notes of the Censors and appeals to their decisions. In addition, the long list of participating cineastes includes Professor Kevin Rockett (TCD, Emeritus), former Censor Sheamus Smith (1986-2003), and recent Directors of Film Classification.

Each of these elements combine for a very compelling, often humorous, film.

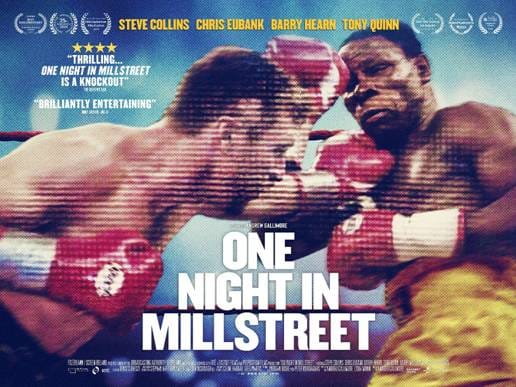

In the Opinion of the Censor is directed by Andrew Gallimore (One Night in Millstreet (2023)), and Lydia Monin. John Kelleher presents and co-wrote the script with Gallimore. John Kelleher Media produced the documentary, supported by the Irish Film Classification Office (IFCO), Oireachtas TV, Coimisiún na Meán, and Caireann Associates.

Kelleher has produced films since the mid-1980s. He produced and co-wrote Eat the Peach (1986), a personal favourite. He served as Censor, too, from 2003-2009. In 2008, duplicating a change made by the British Board of Film Censors in the 1980s, he became the Director of Film Classification in the Irish Film Classification Office. Few are as well-placed to relate the history of film censorship in Ireland.

The Censorship of Films

While film censorship preceded independence, the Censorship of Films Act 1923 was promulgated almost immediately after the establishment of the new Free State. Under the Act, films distributed publicly could be banned or cut if ‘in the opinion of the censor’ they were ‘indecent, obscene, blasphemous or contrary to public morality’.

That legislation, like mass cinema itself, was in many ways novel. It reflected both a general fear of film’s power and a defensiveness about the exposure of the new state and its people to outside forces. In a nation simultaneously revolutionary and conservative, in which competing nationalisms were in a most uncivil combat with one another, foreign films of unknown or unquantifiable influence threatened the citizenry and congregations across the island. Sovereignty couldn’t protect us from cinema.

The Act didn’t apply in the same manner to films shown outside of public screenings (for example, in film clubs) for most of the past hundred years. Where it applied, films were banned or, alternatively, cut before they could be screened. Meaningful, informative classification of films, with certifications for different audiences, developed very slowly. Our modern regime is only two decades old.

An Appeals Board was also established in the Act. This provided a formal opportunity to challenge the Censor’s decisions. In practice however, it also provided a site in which non-state actors, including religious leaders, might exert an informal influence on state censorship. And where films were edited, audiences were often unaware of this adulteration, though many were likely left puzzled by the resulting narrative gaps.

The Law of God and Man

James Montgomery (1923-1940), the first Censor, exemplified these early concerns and constraints. Irish virtue and Irish values, not least those of its dominant religion, were to be protected. And we had to be defended not only from the auld enemy but from those beyond the wave. In fact, he specifically bemoaned ‘the Los Angelesicization’ of Ireland and wrote about ‘The Menace of Hollywood’ later, after leaving his post.

If Montgomery’s concern was sex rather than socialism, the same fear about ‘the “Los Angelization” [sic] of our culture’ was later placed, by screenwriter Paul Laverty, in the mouth of a sermonizing priest in Ken Loach’s Jimmy’s Hall (2014). Set in 1932, the film, accurate at least in this, expressed a concern about the consequences of pernicious outside forces: ‘what is wrong with being true to ourselves, to our deepest roots, our own pure Irish values?’

Early censorship focused on general audiences, young and old alike. The power to create limited certificates, for example, for adults only, existed in theory but this option to classify and to calibrate the Censor’s decisions with more precision, lay dormant for decades. Montgomery later suggested such certification would arouse curiosity, encourage adolescent admissions, and ‘foster[] a contempt for the law.’

Montgomery was particularly sensitive to films that appeared irreligious or overly sexualized or violent. In the Opinion of the Censor pays particular attention to his hostility towards models of womanhood inconsistent with traditional Irish Catholicism. This included the strong-willed Mae West and Scarlett O’Hara (Vivien Leigh). Far beyond Ireland, West challenged gender roles and socially permissible language. And at the end of his long reign, Montgomery gutted Gone with the Wind (1939), like Sherman through Georgia. Not even Fantasia (1940) made it past Montgomery without cuts.

Montgomery’s successor was Dr Richard Hayes (1940-1954), the first of several doctors in the role. As noted in In the Opinion of the Censor, Hayes took much the same approach as his predecessor, as well as requiring changes to film titles. But Hayes also had to grapple with censorship mandated by wartime neutrality and additional legislation when, to paraphrase Hugh Leonard’s novel Fillums (2004), set in 1942, ‘half of the country were neutral on the side of the Germans, half on the side of the Brits’.

At Fillums’ centre is cinema in the orbit of Dublin, including private film club screenings. But when a ‘picture house’ plays Casablanca (1942) for a general audience, the Guards arrive and all hell breaks loose. In fact, as the documentary makes clear, Casablanca was banned on its release under the Emergency Powers Act 1939, for its bias against the Germans. After the war, the film was cut for its immorality, against the institution of marriage. For similar reasons, Brief Encounter (1945) was banned.

From Here to Eternity (1953) was cut, too, including the famous beach scene with Burt Lancaster and Deborah Kerr embracing, wearing little more than the waves crashing over them. In Stella Days (2011), based on Michael Doorley’s Stella Days: The Life and Times of a Rural Irish Cinema (2012), an unedited print of the film plays. As that scene runs, Stephen Rea’s character interrupts, shouting that it was ‘evil American filth’ that was ‘breaking the law of God and man’.

Slouching towards Classification

Montgomery and Hayes were in office for many years; each had had links to Cumann na nGaedheal. Next up was Dr Martin Brennan(1954-1956), a former Fianna Fáil TD, who had the shortest term of any Censor. But little changed with respect to the office’s paternalism. In fact, Brennan banned one in every eleven films submitted. He cut a scene from On the Waterfront (1954), because he believed it inappropriate to show a priest having a beer. He cut another in response to direct intervention by the Catholic Church.

In a period of accelerating changes in cinema and society, Liam O’Hora (1956-1964) continued to hold the line. He made severe cuts to Elvis’ King Creole (1954) and to Tennessee Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958), due to their sexual suggestiveness. In the Opinion of the Censor makes clear that, for the latter at least, such cuts almost certainly left a significant number of viewers confused about the story. Michael Powell's Peeping Tom (1960) and Hitchcock's Psycho (1960) were also severely edited.

The 1960s brought a shift, in Ireland and other countries, towards film classification. For example, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf (1966) was banned by Censor Dr Christopher Macken (1964-1972) but passed, with cuts, by the reshuffled Appeals Board, who certified it for those over twenty-one. Indeed, the Board proved an important counterweight to Macken, overturning thirty of forty-two films banned in 1965 alone. However it would take decades before classification, rather than censorship, was the norm.

If the Board’s flexibility was arguably progress, they were only a little more liberal than the Censor. They overturned a ban on The Graduate (1968), with significant cuts, particularly with respect to Mrs Robinson’s seduction of Benjamin. Joseph Strick’s adaptation of Joyce’s Ulysses (1967) was banned by Macken, a decision upheld by the Board. In Britain, that film was originally rated X (Adults Only) and edited by the British Board of Film Censors before being released uncut in 1970. In Ireland, while it’d been viewed in film clubs, the first general screening didn’t occur until 2001, with the director and then-Censor Kelleher in attendance.

Dermot Breen (1972-1978) was the first Censor with real film experience. He’d managed a cinema and was a founder and director of the Cork International Film Festival. George Morrison’s Irish-language classics Mise Éire (1959) and Saoirse? (1961) both premiered there. Breen continued to cut films. He banned The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973) – a crime classic, with a world-weary Robert Mitchum as a low-level Boston-Irish hood – for its blasphemous language. But, on the whole, Breen banned fewer titles, actively engaged in public debate, and attempted to make the censorship process more transparent.

Following Breen, Frank Hall (1978-1986)’s appointment seemed to promise greater liberalisation. Hall was best known as a satirist, particularly with the popular Hall’s Pictorial Weekly (1971-1980). But he proved another staunch defender of traditional values, especially its sexual mores. Most significantly, he banned Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979), with many critics surprised that he didn’t seem to get the joke.

From Guard Dogs to Guide Dogs

The appointment of Sheamus Smith (1986-2003) marked a real turning point. With experience with Ardmore Studios and RTÉ, he believed film editing should be left to its director, not the Censors. He overturned the earlier ban on Life of Brian and certified The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), without cuts. But he also banned Natural Born Killers (1994) for its violence, a decision upheld on appeal.

Another important moment in classification, not noted in the film, was the release of Neil Jordan’s Michael Collins (1996). Despite what Smith called ‘scenes depicting explicit cruelty and violence along with some crude language’, he passed the film with a PG (parental guidance) certificate, along with a press release explaining his decision. He said that the ‘historical significance’ of the film, along with the hope that it would reach ‘the widest possible Irish cinema audience’ made this decision appropriate.

Which leads to Kelleher, the ninth and final Censor (2003-2009) and the first to get the post by way of an application and interview process rather than appointment. Kelleher was uniquely aware of the potential influence of cinema. Eat the Peach (1986), co-written and produced by him, was based on a true story of two Longford men who built a motorcycle Wall of Death in the 1970s after watching Elvis’ Roustabout (1964). He might reasonably have feared what might be called the Las Vegasation of the country; in fact, Niall Tóibín’s character (Boots) in the film attempts to pass as an American.But during Kelleher’s term, classifications were clarified (2004) and the office’s independence was affirmed. The certificates long displayed before films, complete with the Censor’s signature, were replaced with modern classifications. He didn’t avoid controversy entirely. In the Opinion of the Censor focuses on his certification of 9 Songs (2004) without cuts, despite the controversial unsimulated sex between its leads. But with allies before and after, Kelleher was an important figure in moving from, as he’s put it, guard dogs to guide dogs.

Looking for Mr Censor

Banning hasn’t entirely gone away, you know. Earlier this year, perhaps appropriately on April Fools' Day, TD Liam Quaide (Cork East, Social Democrats) asked the Minister for Justice Jim O’Callaghan (Dublin Bay South, Fianna Fáil) ‘for a list of movies, television shows and video games currently banned by the [IFCO]’. This was part of a wider discussion of the vestiges of state censorship of all types.

The Minister’s written response included an IFCO ‘List of Films Banned from 1973 to Date’. These forgotten flicks include soft porn and kung fu movies, as well as contentious titles like La Luna (1979) and Bolero (1984). But there are some surprises: Looking for Mr Goodbar (1977), Working Girls (1986), and Bad Lieutenant (1992) are there, as is Rosemary’s Baby (1968), banned as late as 1977. Maybe as an oversight, perhaps because of a typo, is the sacrilegious Friends of Eddie Boyle [sic]. Jaysus.

The state censorship of films played a significant role in what Irish audiences could enjoy and engage with over the last century. In the Opinion of the Censor is an entertaining, engaging account of the movement from censorship to classification. In better contextualizing the considerable cultural changes that’ve occurred, here and elsewhere since 1923, it’s also an invaluable historical resource. At least in my opinion.

The film premiered on 30th May at the Irish Film Institute. It’s currently available online at the Oireachtas TV website.